THE WILD HOME STRETCH OF THE OCEAN RACE

Herb McCormick interviews North Sails President Ken Read as the Ocean Race heads into their final sprint of the 2023-23 edition.

It all comes down to a pair of final, demanding races. After five grueling stages and some 30,000 nautical miles of racing through some of the world’s most tempestuous oceans, the final two European stages of The Ocean Race will present the sailors with a pair of courses that offer a fresh set of challenges and obstacles. The penultimate stage, Leg 6, which began on June 8th, is a relative sprint: an 800 nautical-mile test from Aarhus, Denmark, to a “fly-by” turning mark in Kiel, Germany, and then a dash out to the North Sea to a finish line off The Hague in the Netherlands.

And then, the Grand Finale. With a June 15th start, Leg 7 is an especially tricky racecourse, a 2,200 nautical-mile voyage that begins off The Hague; slides through the English Channel and into France’s notorious Bay of Biscay; rounds Cape Finisterre and blasts down the wild coast of Portugal; slips through the historic Straits of Gibraltar; and concludes in Genova, Italy, after one final passage up the always unpredictable Mediterranean Sea.

North Sails President Ken Read, from his current vantage point in Europe at the Georgio Armani Superyacht Regatta in Sardinia’s Porto Cervo, has a unique and informed perspective on this interesting home stretch. Having competed in a trio of round-the-world contests, the last two as skipper of the PUMA Ocean Racing crew in 2008-09 and 2011-12, Read knows exactly what it’s like to wrap up a long, difficult race around the planet. On the eve of the concluding legs, Herb McCormick spoke to him about what lay ahead for The Ocean Race teams.

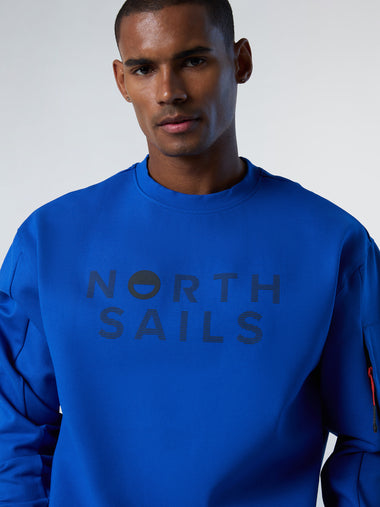

📸 Ian Roman

HM: After all the high-seas, long-distance adventures, these final two legs seem to be a completely different challenge. How do you approach them?

KR: You have to totally shift your mentality. I've always thought the mentality between coastal racing and distance racing is almost like approaching two different sports. It has to be a complete mind reset for all these crews if they want to be successful.

HM: After all the open-ocean miles, now you’re surrounded by land, you’ve got inshore currents, it’s all different. How do you switch gears?

KR: Good question. It’s basically like around-the-buoys racing versus distance racing. The buoys just happen to be points of land and different stretches of water. When you do your pre-race strategy and homework, you spend at least half your time on how to leave and how to enter these different waters. Because this is where you can make big gains or it can get tight as hell if you’re not careful. So, you’re searching for local knowledge, introducing yourself to local sailors you’ve never met who’ve sailed there for their entire lives. I guarantee all the teams have developed their own little coaching staffs for each of those venues they’ll be entering and exiting. You take in as much information as possible and then see what’s applicable and how it plays out. The whole race becomes one big leave and enter.

HM: Leg 6 is an 800-miler, so maybe three days of racing. You need to be on top of your navigation, aware of the competition. Is there any rest for the weary in there?

KR: No, these are much harder races, both physically and mentally, than out in the open ocean. Everybody keeps talking about how wildly uncomfortable this generation of boats is, how violent they are. Because you won’t potentially be in big waves, that may be easier. But the tactics are so taxing. When do we tack? When did they tack? Do we cover? What are our convictions with regard to the next shift? You almost aren’t doing watches anymore because the skipper/navigator designees will get almost no sleep. It’s hard. Really, really hard.

📸 Antoine Auriol / Team Malizia / The Ocean Race

HM: Finally, we have Leg 7, some 2,200 nautical miles, they’re predicting a 10-day race. So, you’ve suddenly gone from a little sprint to a trip that’s as long as crossing an ocean, but next to stuff you can bump into almost the entire time. Take me through that from a skipper’s perspective.

KR: Let's just make the assumption that the top three boats are still super, super close. It's almost how bad you want it. That’s how much sleep you get. I remember some of our shorter last legs, there was literally no sleep. And, even if there was a break and you were power reaching, you’re hiking out, because every tenth of a knot is going to make a difference. This isn’t about playing the correct weather system. So even if it’s 2,200 miles, it’s a totally different animal. I love it, but it’s as hard as you want it to be. And I’m guessing these top three boats are going to make it as hard as possible because they aren’t going to stop sailing the boat as if it were a flat-out race.

HM: I know you’ve sailed most of these waters so I’d like to know the first thing that comes to your mind when we break down features of the coast. For instance, the shipping lanes of the English Channel?

KR: Talk about no sleep (laughs)! There’ll be all kinds of restrictions as to where they can go. We had to go out through the shipping lanes in the channel once, and I remember being so exhausted, we almost ran into a windmill in the middle. Because we were shot, with just the continual tacking or continual jibing. We know how hard it is just to maneuver these boats, period. With the shipping lane restrictions, it’s nonstop. So how deep is your crew? Deep enough to help you make decisions when you do have to finally put your head down from time to time so you don't miss out? There are lots of cases where boats busted their hump to get through shipping lanes and then relaxed and blew it all within a couple of hours for missing the next shift because they were so mentally and physically shot that the key players had to go get some rest. So, yeah, a different, hard game. You just brought up one of the hardest parts of the game.

📸 Amory Ross / 11th Hour Racing Team / The Ocean Race

HM: From there we head into the Bay of Biscay, which has famously kicked many a French solo sailor’s butt on long-distance races.

KR: Well, they don’t call it ‘the Bay of Certain Death’ for nothing (laughs). Listen, the Bay of Biscay is either going to treat you kindly, or it’s going to kick your ass. It’s one or the other. It's all just dependent on the next low coming across from the Atlantic and how it builds up. So, that's hit or miss. It could be a shellacking or it could be a beautiful sail. I’ve had both.

HM: And then we go outside and down the coast of Portugal where we all have seen the massive seas and the big-wave surfers down along that coast. Had a look at that before?

KR: Of course. That, traditionally, is a pretty strong, pretty breezy area, but it can also offer you some of the most beautiful sailing you’ve ever done in your life. There’s a reason why people go train out of Cascais and places like that. Just amazing, high-speed sailing conditions. But say you get there and you’re way ahead on the leg. Do you preserve your assets? Because these boats have proven to be not only exceptionally fast in the right conditions but if you don't treat them with respect, they’re fragile as well. Remember, the IMOCAs were made for single-handed sailing and all of a sudden, these full crews are pushing them harder than they’ve ever been pushed for 24 hours a day. So, if you're a front-runner, what’s the call? You’ve got to have a strategy. Are you ahead? Behind? Do you need to push? Preserve? That’s a big deal.

HM: Which brings us to a rather famous, historical nautical place called the Straits of Gibraltar.

KR: Yep. Again, some really narrow shipping lanes. They'll probably have course restrictions to keep you out of oncoming shipping traffic so probably even narrower. You might drift through or get 45 knots. It could be upwind, it could be downwind. Some of the worst conditions I’ve ever seen in my life were around there, both on the outside and the inside. People who say that the Med is just a cakewalk haven’t seen the Med that I’ve seen a few times. Tactically, it’s really touch and go. A fascinating place to go through.

📸 Antoine Auriol / Team Malizia / The Ocean Race

HM: And that sets us up for the famous final scene: across the vast Mediterranean Sea to the finish line. What’s your take on this last leg as these guys regroup and push for the final finish line?

KR: You could literally see the makings of a Mistral would come up within hours. You might be drifting, you could be holding on for dear life. At this stage, you have to approach it as all options open. An interesting part of this,that the sailors may never admit to, but they’re also starting to think, holy crap, we’re going to live through this! We've just sailed around the world! The enormity of what they’ve accomplished, including these last couple of legs, will start to take effect. It's a big deal. The hard part is over. It's just a tactical sailboat race now. It's what we learned in an Opti. It’s what we’ve done our whole lives. Just sailboat racing. But it’s different, too. I remember pushing so hard those last few kind-of coastal races, but at the same time thinking, ‘Man, oh man, this is amazing. Let’s just reflect a little bit on what we've just done.’ I hope every sailor doing this race takes time to reflect on that. It’s a hell of an accomplishment: win, lose or draw. They should all be very proud of what they’ve done.

HM: Okay, it’s basically a three-boat race now, with Charlie Enright’s 11th Hour Racing holding on to a one-point lead over Team Holcim-PRB with the dangerous Team Malizia lurking in third. What’s going to happen?

KR: If I’m in Charlie’s shoes, I’m considering this regatta starting all over again. I have to figure out how to go upwind and downwind in light air, what’s my drifting sail? Maybe they’ve saved a card or two for now and have a specialty sail ready to go. Team Malizia is set up for big breeze, the Southern Ocean, they’re going to need their correct conditions. Holcim and 11th Hour are more all-purpose oriented; they know each other’s strengths by now. Don’t be surprised to see someone take a chance early, because if they know it’s a flat-out drag race, they might not have the horse for this course. It’s going to be fascinating to watch unfold.