NORTH SAILS BLOG

Tutto

Events

Guides

News

People

Podcast

Sustainability

Tech & Innovation

Travel & Adventure

guides

MELGES 24 WORLDS LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

MELGES 24 WORLDS LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

What To Expect In Villasimius

North Sails Expert Giulio Desiderato provides his intel on what competitors should expect at the upcoming Melges 24 World Championship.

It is hard to say exactly what we expect to see at the Worlds. The pre worlds event was my third event in Villasimius this year, and each time I’ve sailed here we’ve had different conditions – a strong Mistral, strong northeasterly with flat water, light sea breeze, big waves, and even one time with wind from the south. Each day at the pre worlds the wind was out of a different direction, so it will be very interesting and we should expect a variety of sailing conditions.

Because Villasimius is not a very common place to hold regattas, there isn’t really any local knowledge as not a lot of people of sailed here very often. This means it will be an open playing field when it comes time for the championship. It could be anyone’s game, which will be exciting.

I’ve sailed here in the tactician role and as main trimmer, and now most recently I’ve coached. What I’ve observed over those experiences on the boat and from the sidelines is that if the wind comes from the North, it will be really important to keep an eye on it and try to figure out which side the newest pressure will fill in.

During this time of year in Sardinia, the wind can be anything. The sea breeze is still common, but because of where Villasimius lies geographically, it is close to a cape and exposed to storms and wind lines that can be frontal and come up quickly.

Tips For Clients:

Manage your risks and get a good start. It will be important to manage your risks with the large fleet. Avoid big mistakes during the starts, and focus on finding a good place to get a clear lane off the line. Ideally, if you can start and sail for three minutes straight before having to make any moves, this will be key.

Keep an eye on pressure. Try to figure out where it’s coming from most often. They may drop the windward mark in an area where the pressure is filling in, which may put you on one particular side of the race track.

Tuning. Don’t be afraid to adjust your rig. If you try different settings, you can find what works best with the conditions at the time- which are going to be changing a lot at this location. It could be beneficial to set up for a certain condition knowing you’ll see it at the top-end of the course.

Sailing with 3Di? With 3Di, you won’t have to play with your tuning settings as much as teams using paneled sails will. We always use the same numbers. Our jib track setting also remains the same. The benefit is that there is not much play required. It is very user friendly.

Recommended Sail Inventory

For the championship, I recommend the following inventory: Mi1 mainsail, Ji-2 Jib, P-1 and P-3 Spinnaker.

Have questions about sails? Interested in upgrading your Melges 24 inventory to Championship-winning sail power? Contact your local expert today.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/24 WORLDS LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

J/24 WORLDS LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

Get To Know Biscayne Bay

To help you prepare for the 2019 J/24 Worlds, we asked the local Star and Snipe World Champion Augie Diaz to explain about his home waters of Biscayne Bay in Miami, FL.

Biscayne Bay is I think pretty straightforward. The weather is driven by cold fronts approaching, and we don’t get as much breeze as we used to because the city’s grown so big. But generally, any breeze from the northeast around through the southwest is great sailing. From this direction, the breeze is usually under fifteen knots, with relatively flat water (chop but no swell). Spring and fall are the best seasons, because we don’t get many fronts.

Dominant wind direction: easterlies

The old rule of thumb is still the case: if the wind’s to the left of the south end of Key Biscayne, you go left. Near the Key, from 120-160 degrees, there is a little more pressure closer to the end of the Key, and also a geographical shift off the land. How favored is somewhat current-dependent; from 70 degrees to 160 degrees with an outgoing current, then left is really good, what we call the “Old Man Expressway”. At the top of the beat on the J/24 Worlds course, the Old Man Expressway could be important.

On what I call the Cuba Course, where the Etchells sail, way down south of Matheson Hammock, there’s less left down there than there is closer to the point of Key Biscayne. So you have to keep in mind where you are on the Bay.

Current

Understanding the current is very important. People think the current comes in and out of the Bay from the east, but it actually runs in and out from Bear Cut. If you get close to what we call the Valves, which are the channels through the shallow areas that on the chart are labeled Biscayne Flats, there is a component of current going in and out of there. But you have to be very close to the Valves for that to be the net effect. Otherwise, the current basically ebbs from the southwest to the northeast, and goes the opposite way when it floods.

As for the timing relative to high and low tide, I’ve seen it as much as an hour off, so I just use tide change as a gauge and then keep checking the buoys, all the time. Sometimes seaweed will show lines of current, but I’ve never really seen a change in the color of the water.

Other wind directions

Once the wind gets to about 170-180, it’s pretty important to protect the right. That’s true all the way to 220 degrees. Anything right of 220-230, it’s going to march quickly to the northwest because that’s a frontal-driven direction, which doesn’t doesn’t have the ability to stick.

If the wind’s right of 230 degrees, I like coming in from the top left because you get some really nice puffs off the left shore. It depends where you are on the Bay; on the J/24 course, close to the west shoreline, you’ll definitely want to come in from the top left.

Northwesters are like you’re on a lake: very shifty, very up and down. But in late October, it’s actually less frontal, so that’s less likely.

Secret to success

Focus on what the current’s doing, and in the easterly understand how important it is to go left.

Thanks Augie!

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

HOW TO BUILD YOUR MOTH SKILLS

HOW TO BUILD YOUR MOTH SKILLS

Dan Neri Explains How To Get Started Sailing this Foiler

Compared to most dinghies, building the basic skill set for the Moth takes a long time. After about 40 hours of sailing the Moth, I can foil with confidence in all directions in the limited window of 8-14 knots of wind. I feel like I am close to executing a foiling jibe but have not connected two of them yet, and every tack is still an adventure with a surprise ending.

The experienced Moth sailors tell me that I am on a typical timeline. I was told that my decades of Laser sailing would help, but I don’t recognize a lot of cross over to the Laser. A skiff sailor will get there more quickly. Younger sailors probably learn faster than older sailors, but older sailors can afford to replace the broken parts! It all evens out.

Here are some lessons I have learned in my first nine months of Moth ownership that might help a fellow beginner.

First Assembly: Study the boat manufacturer’s assembly guide. Then get an experienced Moth sailor to help you. Plan on two full days. Take your time and you will break less parts.

Rigging: Watch the Nathan Outteridge tutorials. Then get a Moth sailor to help you the first time.

(And make sure to read How to Rig a Moth in 20 Steps)

Launching: Watch the Nathan Outteridge tutorials. Rig up in your yard and practice carrying the boat around in an area with no obstacles. You will find a balance point with the boom and mainsheet on your shoulder and the mast tip and wing bar both off the ground.

Flight setup: Get a Moth sailor to help you set the ride height control (see Flight Controls below). Pull the wand all the way up. Put the gearing in the middle. Then forget about the flight controls, and pretend it is a regular dinghy.

Balancing the Moth at low speed: Look for a day with 8-10 knots of steady breeze. Practice low riding while focusing on keeping the wings out of the water. Learn to tack at low speed. Hint: you can not scull with a Moth rudder. Try to not get stuck out on your Moth in less than six knots of wind. The Mach II is happier in reverse than in forward in very light wind.

Foiling: Watch the Nathan Outteridge tutorials. Look for a 10-12 knot day. Less than 10 knots makes taking off tricky. More than 12 knots feels like a hair-on-fire experience until you get some confidence.

Plan to sail for one hour with equal time spent swimming and foiling. Sail back and forth on a beam reach and enjoy the ride. Upwind and downwind can wait for another day; the first sensations of liftoff and controlled flight are the foundation that will keep you working up the steep and frustrating learning curve.

Turning downwind: This might be easier for sailors with skiff or catamaran backgrounds than it was for a lifetime Laser sailor, but the upwind-to-downwind transition is where I’ve had my most violent crashes. It is mostly a matter of starting with windward heel and then committing to the maneuver. The more breeze there is, the more aggressively you need to move through the transition zone. Waves make it more exciting. If you don’t go home with a few bruises, you probably did not progress. Get comfortable making the turn up and down in 10-12 knots before you try it in 14-16.

Foil Jibing: Watch the Nathan Outteridge tutorials. Then plan to crash a lot.

The maneuver has a few distinct steps; get moving at maximum speed with a slight windward heel, set your back foot on the hull and tuck your front foot, swing the tiller extension to the new wing bar, and lunge across and under the boom. Let the boat carve through the turn while getting your butt fully onto the new wing bar, then switch hands. While doing that make subtle steering adjustments, pushing the tiller slightly toward whichever wing bar is higher, to keep the boat under the rig. Simple.

Sail Trim: The Moth is extremely sensitive to sail trim, but for me, there was so much other stuff to deal with (balancing the boat in particular) that I took a set-it-and-forget-it approach at first. That was a mistake. Sail trim makes a huge difference in lighter wind by generating take-off speed (with a powered-up sail) and then by reducing drag and heeling moment once you are foiling (a flatter sail than you’d think). Again, the learning curve is steeper than other boats. To make sail trim adjustments, you have to learn to grab the right control lines (vang and cunningham) without looking down to find them, and then you have to pull two feet of line without upsetting the boat, while steering with the mainsheet in your tiller hand. Easier said than done.

Flight Controls

There are four controls that dictate lift-off and ride height.

1.) Ride height adjustment: It’s critical to set the ride height adjustment barrel in the correct position. The ride height mechanism connects the wand to the main foil flap. The ride height range is set while still on land but after the boat is fully rigged, on its side. Once the range is set correctly, you can dial in a little more or less lift with the control line while sailing.

The ride height adjustment controls the position of the main horizontal foil flap. If the linkage is set with the rod too long (barrel screw opened up), the flap will be pulled up (no lift) and the boat will not take off. The opposite adjustment (barrel screw closed down) creates too much lift (a big gap between flap and vertical foil indicates the flap is pushed down, making a lot of camber) which will cause the boat to lift off and keep rising until the horizontal foil catches air (and you crash).

The long black barrel is a telescoping screw that changes the length of the wand connecting rod. The barrel is turned by the control lines wrapped around it that lead out to the starboard and port wing bars. The aft end is connected to the curved arm (between my hands in this picture). The curved arm connects to a vertical rod that is in turn connected to the flap on the main horizontal foil. The “gearing” adjustment moves the ride height barrel up or down on the curved arm. A lower position results in more direct response between the wand and flap, while a high position dampens the action. Got it?

Experienced Moth sailors set the ride height by eye and it is a bit of a black art. If there are no expert Moth sailors available, adjust the barrel so that the flap and forward part of the foil form a fair curve when the wand is angled back about 45 degrees. Another gauge on the Mach 2 is to measure the gap between the flap and the vertical foil, which should be about 7mm with the wand all the way forward.

This shows the camber amount needed when you are up on the foils with just enough lift to keep you flying, with the wand hanging straight down and ticking the water.

Set up your ride height control line so that this neutral lift position is at the middle of the range of adjustment. If the breeze is very light, dial in more lift. If the breeze comes up, dial out some lift. As a newbie, it is easy to second-guess the ride height adjustment when in fact your technique is the problem, or to assume your technique is bad when in fact the ride height is way off. Get some help, so you can have confidence in this setting and focus on sailing.

2.) Gearing: Gearing comes into play once the boat is flying. Anthony Kotoun explains the function of the gearing control as “how much information do you want the wand to deliver to the flap.” If you find your boat is bouncing when passing over small surface waves, you have too much gearing (the flap is moving too much). If your boat is too floaty and slow to respond, the flap is not moving enough and you need to pull the gearing control down. Setting it in the middle is a pretty safe bet.

On my boat, the gearing control is the red line. If you follow it forward (towards the lower left of the photo) it connects to the black slider that is pushing down on the ride height adjusting barrel, along the curved arm. Most boats have the gearing led to both wing bars for adjustment on the fly. For now I leave it in the middle, so I have less lines to get tangled in!

The blue control line adjusts the shock cord that pulls the wand forward. In very light air, you want very little tension on the shock cord; as the breeze comes on, you want a little more. Worn shock cord makes the boat hard to control in windy conditions.

3.) Rudder angle: The rudder pin (the long pin that goes through both the upper and lower gudgeons) slides forward or aft in the rudder head, which changes the pitch, or angle of attack, of the foil at the bottom of the rudder. Changing the pin position and foil pitch controls the fore and aft flight trim. With the pin forward the rudder head moves aft, which in turn tips the foil up and creates more lift. More lift results in easier take off and more bow-down fore and aft trim. Moving the pin aft causes the rudder foil to sink and makes the boat fly with the bow higher than the stern. The pin position is adjusted by a big plastic screw inside the tiller, which is adjusted by twisting the tiller extension.

4.) Wand Length: The wand is telescoping with the length adjusted by a continuous-loop control line led to both wings. Shorten the wand for a lower fly height (better control but more drag and lower speed) and lengthen the wand to fly higher with greater righting moment and less drag (higher speed).

Left: shorter wand, lower fly height (better control, but more drag and lower speed). Right: long wand = higher ride height.

That probably seems like an awful lot to learn. It is, but it is also much easier to understand once you get your boat rigged up and laying on its side at the water’s edge. Pre-launch set up and check over is the only part of the Moth sailing game that you can learn while comfortably on land, without fear of crashing.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

HOW TO RIG A FOILING MOTH

HOW TO RIG A FOILING MOTH IN 20 STEPS

Dan Neri Gets Ready to Sail this Singlehanded Foiler

When I first set up my Moth, I broke a lot of stuff. Since then I’ve learned what to do (and what not to do) and in what order. First, bring everything to the beach. Set the foils off to the side, safely out of the way of the boat and any spectators.

Rig sail and spreaders

1. Slide the mast into the sail, keeping the mast above all the camber inducers. It is easy to get the mast past the lower cams. You’ll have to shove it past the top two one at a time.

2. I keep a string with a couple of spliced loops in my pocket to use as a temporary cunningham. I pull it just enough so the spreader bracket is positioned in its sleeve cutout. After stepping the mast this string is replaced by the regular cunningham.

3. Push the cams onto the mast and zip up the sleeve, starting at the top (when you derig, take them off starting at the bottom). To load the cams, put the mast on your knee, push down on the batten (against your knee) with one hand and push up on the cam with the other hand.

4. Before you lay down the sail and walk away, make sure the battens are pushed down so the sail doesn’t fly down the beach.

5. With the sail laying across the wing bars, untangle the stays, install the spreaders, and then attach the forestay and side shrouds to the mast.

Step the mast

Note: My boat has an adjustable headstay, so I can step the mast with the headstay adjustment at its loosest setting. If you have a fixed headstay, you’ll need to use a longer temporary headstay.

6. Position the boat so that it is pointing about 10 degrees away from head-to-wind. Hook up the shroud on the windward side and the long headstay. Pick up the mast between the two attached shrouds with the masthead into the wind, put the mast butt into the step, and push the mast up into place.

7. The wind will do most of the heavy lifting and the mast will fall to leeward, toward the loose side shroud. Hook up the leeward shroud, but leave the headstay long until after you attach the clew to the outhaul.

8. Attach the boom to the gooseneck and then hook up the cunningham and pull it tight. The tight cunningham will help to bend the mast and make it easier to hook up the outhaul.

9. Attaching outhaul to clew requires three hands; two hands to pull the sail and boom together against the boom vang, and a third to install the clevis pin. I have learned a little trick; I set the boom in the crook of my elbow and simultaneously pull down on the leech with that same hand, until the clew grommet lines up with the outhaul car. Then I install the pin with my other hand. Don’t forget to tension the headstay.

Install blades

10. If you’re rigging on a beach, remember to put a flat rock or a towel or anything other than sand under the tip of the bowsprit and the wand axle bolt. Then capsize the boat so you can install the blades.

11. Make sure the sail battens are popped down so the sail does not lift the boat. Tighten the mainsheet so the wind is pushing the sail towards the ground.

12. Assemble tiller/rudder and install on transom. Remember to put the tiller under the shock cord.

13. Take away the dolly and insert the main foil into the slot. Insert the daggerboard retaining pin. (You may need a hammer to tap it in if you are having trouble lining it up perfectly.)

Final adjustments

14. Hook up the ride height adjuster and gearing (on the floor just aft of the mast).

15. Pull the gearing to the middle of the range.

16. Attach the ride height uphaul/gearing cap.

17. Pull a little tension onto the wand shockcord.

18. Use a stiff ruler to check the foil flap gap with the ride height adjustment barrel control line in the middle of its range. For the Mach II, with the wand all the way forward, a 7mm gap is a good starting point.

19. Install a GoPro on the tiller so you can compare yourself (unfavorably) to the Nathan Outteridge tutorial videos.

20. Go find your hat if you are bald, and your cheapest sunglasses. Take off the foil covers. Ready to go sailing!

Read Moth Newbie: Dan Neri Learns to Foil

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

THE BASICS OF SAILING THE IC37

THE BASICS OF SAILING THE IC37

2019 Rolex New York Yacht Club Invitational Cup

With more than 30 boats sold, the IC37 is officially the next big thing in one-design keelboat racing. This Mark Mills design is purpose-built for close racing in large fleets. Strict class rules that mandate mixed-gender, amateur crews and limit teams to one set of three one-design sails per year are intended to level the playing field and create a competitive environment where the team with the most talent and dedication and teamwork wins, rather than the one with the largest bank account. The first few years of a new class are always a time of tremendous learning and the IC37 class is no different. The winning techniques are evolving regatta by regatta. Here is a overview of the boat and the core maneuvers required to get around the racetrack.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

MELGES IC37: REEFING MADE EASY

MELGES IC37: REEFING MADE EASY

Step By Step With North Sails Ken Read

📸 Melges Performance Sailboats / Sarah Wilkinson for Beigel Sailing Media

With just three sails for all conditions, the ability to reef both the main and jib of the IC37 is crucial to sailing the boat in heavier air. The best way to properly de-power your boat is to reef your sails, and North Sails has done everything possible to make this an easy adjustment. Class rules state that in 18-20 knots, the Race Committee can display code flags which mean you need to reef your sails before the starting sequence.

From the time they hoist the “V” flag (which means reef your mainsail) or the “J” flag (which means reef your jib), you’ve got 10 minutes to reef before the start of the sequence. North Sails President Ken Read explains the process for reefing your sails on the IC37 in this latest how-to video. Learn how to do it and be comfortable setting it up so when the time comes, there is no question when you are out on the racecourse.

See also: North Sails Tuning Guide for the IC37

Learn more about the North Sails products for the IC37 by Melges.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

INTERNATIONAL MOTH SPEED GUIDE

Moth Dinghy expert Rob Greenhalgh introduces this extraordinary singlehanded foiling dinghy and describes the keys to sailing one fast.

Who sails the foiling Moth Dinghy?

The Moth class is for everyone—it’s so exciting, you don’t need to race it. Club sailors can get a huge buzz out of foiling, going fast around the bay, and learning to foil jibe and tack. They might enjoy it so much they never need to join a race. At the other end of the spectrum, there are sailors who have been in Moth Class for a decade or more and love the challenge of racing this exciting, complex craft.

Viewed from stern or bow, the foiling moth is a high-speed machine, clearly unlike other sailboats.

What kind of sailors enjoy this challenge?

Moths are development boats, not a strict one-design class, and that’s daunting for some. The technical and evolutionary side of Moth sailing requires a good understanding of how everything works—how the foils interact with the rig setup and how to balance both aspects. Over the last five years, there have been massive speed advancements, which will continue. To be at the top of the game, you have to enjoy the technical side. But you can buy equipment off the shelf and, if you practice and sail well, soon be up to pace. Though more technically oriented sailors often gain an edge for a while, there are also lots of people who will make changes that don’t help them, so it evens out.

How physical is the sailing?

When you are first getting into it, Moth sailing seems physically hard, but once you’ve done it a while, it’s not too bad. On a windy day with a lot of capsizing, it gets pretty tiring. But it’s a light boat, and the loads are not high. Anyone can do it if you can move quickly at times. There are plenty of Moth sailors in their 60s.

New boats or used, which are better?

My advice for the first-time or second-time buyer is to look for a good second-hand boat that you know will fly. This saves you a lot of effort, because even experienced Moth sailors need a few months to work up a new boat. Sure, it’s always a worry that you might not be getting good enough kit with a used boat, but in my experience, any modern Moth can be made fast. If you want to buy new, a standard boat from either of the two main builders—Exocet by Maguire Boats, or Mach 2 by MacDougall McConaghy—will quick enough for top 5. You can also have a look at the new Bieker Moth by LSF Composites.

The Moth is a development class. What’s happening lately?

At the top end of the class, mast lengths are getting shorter to lower the rig’s center of effort and improve performance. A shorter luff length results in a longer boom length. Rigs have progressively become lower over the last five years, and mast lengths have reduced from 5270mm or 5300mm to the current standard of 5100mm.

The Vi-8 DS 3Di (on top) and Vi-8 LA 3DI feature the same sail area. The LA has more power in lighter winds to foil more quickly; the DS has less drag at high speeds.

What sails do you recommend?

North offers four different sails that meet the Moth sail-area limit of 8.25 square meters. (For more detail, read Four New 3Di Sails for Moth Sailors.) The choice of sails relates to your weight, expected wind speed, and another ongoing development in the class—deck-sweeping sails. Because of the class sail-area limitation, in 14 knots of wind we are always trying to shed horsepower and reduce aero-drag. The deck-sweeper sail is better at that, cleaning up areas of drag around the front of the mast, the boom, and the deck area.

North’s Vi-8 DS 3Di sail is a decksweeper-style sail that reduces aerodrag. If you weigh less than 75kg, you can use the deck-sweeper the whole time. If you’re heavier, like me, in breeze less than 10 knots you’ll need the all-purpose sail’s extra horsepower to get up and foil. The deck-sweeper sail has less horsepower because its center of effort is lower and its shape is not quite as good in those low areas around the mast, boom and deck.

8LA-3Di provides extra power to get on foil.

Which sails do you use?

I use the North Vi 8LA 3Di and Vi-8 DS 3Di, as both fit my mast length of 5100mm. They can be used on both the Mach2 and Exocet.

The decksweeper (Vi-8 DS 3Di) creates an endplate and lowers aero-drag. It is slightly faster once foiling.

How does foil choice affect sail choice?

Moths have two foils, a larger foil for lighter winds and a smaller foil for stronger, and that’s a choice you have to make on the beach. In my case, if I expect to be on my foils all day, I’ll choose the smaller foil and the deck-sweeper sail. If the winds are lighter or less reliable, I will often choose the big foil and the LA sail. And if I expect light air to start but a building breeze all day, I’ll likely choose the big foil with the deck-sweeper sail.

Tuning the Moth Dinghy

What are the keys to tuning a Moth?

Generally speaking, you should set up your boat to carry as much rake as possible. How much is that? You’ll know it’s too much if you can’t get under the boom in tacks and jibes. This is not something you do underway, and if the boom is making boat handling more difficult, make the rig more upright until that smooths out.

What other key adjustments do you make before launching a Moth?

Batten tension is one. For Batten 1 (the top batten) down to Batten 5, just take the creases out of the batten pockets—don’t over-tighten them. For Batten 6, remove the crease and then add two more turns by twisting the batten key two full revolutions in a clockwise direction. For Batten 7, take the creases out and add three turns. The outhaul is also non-adjustable underway. Rig the boat ashore with the outhaul loose. Pull on max vang and max cunningham, and then pull the outhaul tight. This will give you a good all round setting.

What other settings can you recommend?

Here some of the numbers from my boat, but don’t worry if your measurements are different. Comparing measurements boat to boat may not matter at all. The important thing is to start recording them and experimenting.

Front Prodder 340 (adjustable +/-50mm)

Side Arm 410mm

Deflection 220mm

Shroud Base 1500mm

Mast Length 5100mm (excluding plastic plugs top and bottom)

Back of mast to clew ring 2340mm

From mast length to shroud base, it's important to record all of your boat and rig measurements. You will change them over time.

How do you set up your foils, actuator wand, and gearing?

This could be the subject for an entire article, but here is an introduction. A Moth has main foils on the daggerboard and a wand in the bow that automatically adjusts the angle of the foils as you fly higher and lower. The rate at which your foils respond depends on how you set the gearing in the bow between your wand and the foils, and this is something you’ll adjust depending on your expectations for wind speed and wave conditions—the rougher it is, the more sensitive you want your gearing to be.

Sailing in rougher water requires faster gearing between your actuator and main foils. Foil gearing is a critical control for waves; make sure it can be adjusted for rough waters. To get through waves you need faster gearing. You’ll also change foil size depending on the wind forecast. I have two sets of main foils and use the smaller one on windier days. However, if the wind is light for the first race and predicted to build, I’ll go with the larger foil because the speed penalty of not being able to fly with other boats can trumps all other considerations.

Upwind Moth Sailing

What is most important when sailing upwind?

On any point of sail, the vang and cunningham are powerful controls, and need constant adjustment for different conditions. The goal is to generate power for low-riding and to get up on the foils, and then flatten the sail as the wind builds. One of the challenges of the Moth is it has a maximum 8.25 square meters of sail area, and upwind in most conditions, that’s more sail than you need. Downwind, you have the opposite problem; your speed reduces the apparent wind so much, you’re always starved for power.

What is low-riding mode and how do you sail fast in light winds?

In general you don’t race in winds when you can’t foil, but it may happen that the wind lightens up substantially during a race. Sailing in low-riding mode is an art in itself, something like balancing in a canoe because the hull is so narrow. I always recommend practicing sailing that way.

What does it take to fly a Moth?

To get on the foil, you’ll need a little windward heel to start. If you have marginal flying conditions, shift your weight just slightly farther aft to get more angle on the main foil. Your goal is to get to critical speed to get lift on the foil. Your rig can create vertical lift, so try to tip it over on top of you, but not too far. It’s a bit of a fine line.

Heel the Moth to windward to keep the boat more stable and reduce leeway.

Why do you tip the Moth to windward when flying?

We sail with the rig always tipped to windward because it keeps the boat more stable and reduces leeway on the main foil. Use very subtle steering and trimming of the main.

How do you trim the Moth sailing upwind?

Correct trim is the absolute key to good boatspeed. It’s very easy to over-sheet and stall the front of the mainsail. Always have the inside tell tales lifting. A common mistake is sailing under-powered and over-trimmed. As the wind increases, flatten the main by tightening vang and cunningham to accommodate the higher apparent wind speeds.

How do you adjust sail trim for gusty winds?

You need your rig set-up to be user friendly. That means having enough vang and cunningham to straighten the sail. If twisted, the center of effort can move up and down the sail. It takes a certain level of confidence to get to the point where you can let go of the mainsheet to tighten the kicker and cunningham.

Downwind Moth Sailing

What is the key to good Moth speed downwind?

Downwind we need a massive gear change as apparent wind speed reduces when you round the weather mark. Upwind, at speeds of 15 to 20 knots, you’ll be sailing in very high apparent wind speeds and fully depowering. Downwind, apparent wind speed is much lower. After bearing away, let the cunningham off completely, over-ease the vang and then ease the cunningham again. The over-eased vang really allows the cunningham to ease up the mast. I then bring some vang back on too avoid too much twist. People sometimes sail too twisted downwind, which makes the sail flat and less stable. I also pull on a tiny bit of cunningham to clean any creases, and as the wind builds, I bring on both controls slightly.

Sailing downwind, be sure to maintain a big entry angle in the lower part of the sail and avoid over-trimming.

What is your focus when trimming downwind?

I focus closely on my lower tell tales, keeping them flying 100 percent and making sure I ease enough to keep the sail ‘hooked up’ with airflow attached. I look for a nice big entry angle on the bottom part of the sail and clean up any horizontal creases by subtly tightening the cunningham. From there, it’s a matter of very subtle trim and steering. If in doubt, ease the sheet and be sure you have good flow going around the front of the sail. If you run into a light patch, just head up to keep the flow going on the main. If needed, power up the main even more. Get the gearing really slow on your foils to minimize drag. The boat will go faster and apparent wind will increase, moving the wind forward and letting you trim harder. Especially when it’s a bit lighter downwind, be sure to pre-empt a drop in apparent wind by easing main and bringing the bow up!

Moth Tacking, Jibing And Gear Changing

How do you foil jibe a Moth?

In all maneuvers, focus on where your body has to end up and getting your hand and foot positions correct. When jibing, think of the foils like they are an airplane; banking its wings is the only way it can turn. You need to tip the boat to leeward as you go into your jibe. As soon as the foils are banked, carve into the jibe with the rudder; the more heel you have, the harder you have to turn. Then move across the boat. Going into the jibe, I put my hand as far along the tiller extension as possible when I pass it across to the new side of the boat, and my body naturally follows. Lead your body with your arm and you’ll come out with the tiller behind your back where you want it and can do the hand transfer. Practice steering behind your back and quickly changing hands out of the jibe. Also, focus on trimming the main nicely out of the jibe so the sail ‘hooks up’ and you get power quickly. Jibing in light air can be hard but once you’ve got it, you can jibe just as easily in 10 knots or 20 knots. Sailing the boat downwind in all wind speeds is quite different. When it is windier, you tip the boat to windward more, move aft slightly, and don’t power up the sail as much. If you can’t foil jibe, it’s probably not windy enough to race. Keep in mind that it’s easier to jibe than tack. Sometimes when sailing upwind, we’ll jibe rather than tack to ensure we can stay on the foil.

When foil tacking or jibing, you need to flatten the boat. For jibing, bank into the turn to leeward. You’ll turn the boat more aggressively when your body is ready to move across to the new wing.

How do you foil tack a Moth?

When tacking you have to move quickly, bringing the boat relatively flat once head to wind. Start luffing slowly, taking the edge off your speed; make sure the boat is flat when head to wind. As my body moves across the middle to the new wing, I’ll increase the rate of turn, steering quite aggressively through the eye of wind, but my body has to be ready to cross the boat and receive the power on the new tack. You need to come out tipped to windward. Here’s how I break it down:

Ten seconds before tacking, consider slowing the boat slightly and sailing slightly higher.

Plan for a slow luff head to wind, followed by a faster turn rate once confident that crew weight can be positioned correctly.

Heel to windward before the tack but flatten the boat once head to wind. Move your weight inboard. It is important here to sheet the mainsheet on centerline so that it is not over the leeward wing when you pass underneath.

As you move across the middle of the boat, pass the tiller extension around the back and into a position halfway along the leeward wing.

When you are confident you can move to the new side, increase the rate of turn, landing on a wider than close-hauled course.

There are a lot of G-forces during this period, so expected to get ejected a few times!

Don’t try to piece the whole tack together immediately. Practice the first phase of luffing head to wind, getting your weight to center, and switching the tiller extension across.

Remember to ease mainsheet out of the tack and have your hands positioned so that the sheet can be eased quickly. The sheet is more important than the tiller on exit.

I set my mast rake to allow 70 to 75cm between the boom and the deck where I cross the boat. Tacking is important, so make sure you have room under the boom! For tacking practice, I recommend having the rig more upright.

Don’t adjust any control lines right before or after tacks, unless it is very light and foiling is marginal.

Name 5 key gear changes in a Moth

To foil early in light air, power up by having the vang and cunningham as loose as possible. However, it is easy to over-deepen the front of the sail, requiring further bear-away to get good flow on the sail. Don’t overdo it.

Downwind always requires a deeper sail shape than upwind, regardless of wind speed.

Once foiling, immediately pull on vang to stabilize the sail and cunningham to clean the creases. Even though the wind is light, we are quickly doing 14/15kts. The AWS is high so we need to change sail shape to achieve good speeds.

As the breeze builds, constantly increase vang and cunningham loads to achieve the desired sail shapes. Max vang should be achieved in 15 knots and max cunningham in 18 knots.

The Moth gets overpowered quickly, and from 18 knots upwards a softer tip or different sail is required. North’s LA and DS designs have a slight variation in the luff rounds to cover the range, with the DS being aimed at 14 knots true wind speed. For lighter sailors, a softer-tip allows the mast to bend earlier and depower the sail.

How do you start a race in a Moth?

Starts are a bit chaotic. Even for long-time racers, a Moth start will be a new experience. People get up on their foils with about 25 seconds to go and do a big turn-up at about 3 seconds, crossing the lining at 20 knots. A key thing when you’re on your foils is to have the ability to slow down while maintaining control. You need to practice that. Getting to the pin too soon is dodgy, especially with boats starting on port tack.

Why do so many Moths start on port tack?

Moths travel at 15 to 18 knots upwind, so tacking is a very costly part of an upwind leg. Reducing the number of tacks during a beat is very efficient, although this depends somewhat on how well you tack and how confident you are in making your tacks.

How many ways can you capsize a Moth?

You will capsize a Moth every possible way when learning. But I can sail for days now without capsizing, unless it is windy and choppy. The key to recovering quickly is to get on the daggerboard and do a dry capsize, climbing back over the wing. Sometimes that’s hard to do, especially when you pitchpole and find yourself 20 meters out in front of that boat.

What is the most common boat-handling mistake in a Moth?

Capsizing! Foil tacking, in particular, is very difficult. A common mistake is trying to foil tack when it’s breezy. Drag is so high that as you go through head to wind, everything slows down and it’s easy to capsize. You may be better off planning to do a touch-and-go tack.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

SPINNAKER SNUFFER INSTALLATION GUIDE

SPINNAKER SNUFFER INSTALLATION GUIDE

Making Your Downwinds More Easy and Enjoyable

© Amory Ross

North Sails cruising spinnakers and Gennakers™ equipped with Snuffer Plus™ spinnaker snuffers make downwind sailing faster and more enjoyable, while saving much of the aggravation normally associated with off-the-wind sailing. When used properly, a cruising spinnaker can add miles to your daily runs. Cruising spinnakers can be quite simple to deploy, even with a short-handed crew.

Step 1: Attach the clew and foot

On a dry, clean, open area), secure the head of the sail to a post and run the leech and luff making sure that it is free of any twists or tangles.

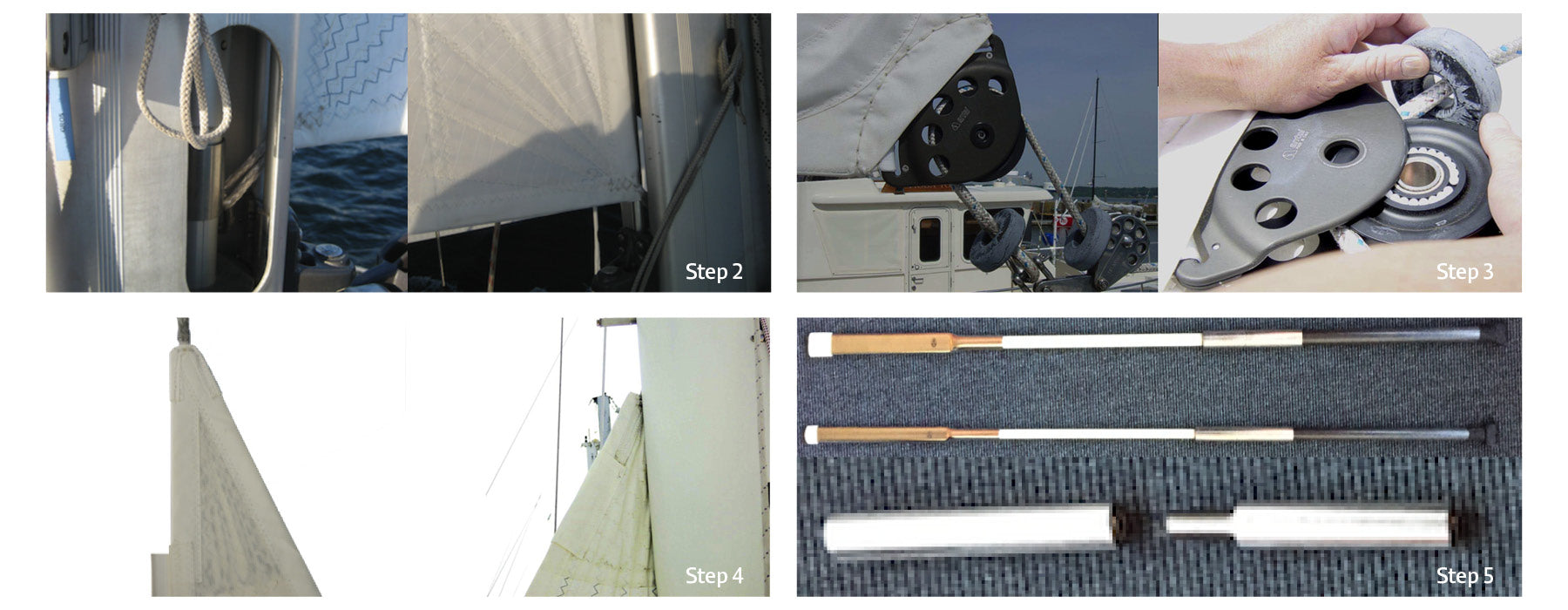

Step 2: Laying out the Snuffer Plus™

In the same way that the spinnaker was straightened, attach the “head”of the Snuffer Plus™ to a solid point and pull the sleeve out making sure it isn’t twisted. Use the colored stripe on the sleeve as a guide.

Step 3: Prepare the Snuffer Plus

Once the spinnaker and the snuffer have been laid out straight, use the internal retrieval line to pull the cone of the snuffer all the way to the head exposing the swivel

Step 4: Attaching the sail

Attach the head ring of the sail to the swivel inside the snuffer. Make sure that the screw or shackle is as tight as possible.

Step 5: “Snuff” the sail

Once the head of the sail is attached, pull the Snuffer sleeve down over the sail making sure neither the sail nor sleeve is twisted.

NOTE: On Gennakers™, the cone will not cover the entire sail and should end approximately one foot from the clew. Allowing the clew to go into the sleeve could risk damaging the cone when the sail is deployed underway. Battens can be taken apart by removing the tape and while holding the back section of the splice connector, flexing the front end up and down while exerting pressure in the opposite direction as the arrow.

Step 6: Loading the sail into the EZ Launch & Store™

Box Turtle

When the sail is ready to be placed In its turtle, lay the turtle out as shown, attaching the tack ring to the green Velcro tab and the clew ring to the red Velcro tab.

Insert the cone of the Snuffer into the bag first. Flake the sail into the bag leaving the head of the snuffer on the top. Use the Velcro tab at the center of the bag to secure the head and Velcro the bag shut. Finally, use the straps on the bag to cinch the bag shut.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/105 NORTH AMERICANS TOOL KIT

Get The Most From Your J/105

The 2019 J/105 British Virgin Islands North Americans in Marblehead is just around the corner. Is your team ready? Our J/105 Tool Kit will help. Created just for J/105 sailors, by our expert team.

#NSVictoryList

There is no better performance test of a one design sail than the results it produces. In 2018 alone, North Sails J/105 inventories helped teams win regattas all over the US.

Tips From The Champ

Champion Terry McLaughlin shares some tips that helped team Mandate win the 2018 North Americans.

Downwind Tips & Tricks

How to sail as deep as possible while still keeping your speed up. Before your next regatta, read this downwind manual from expert Will Keyworth.

Define Your Speed

Pulling all the pieces together can be challenging. Our J/105 Speed Guide will help you leverage our expertise to make the most of your sailing.

Fine Tune With North

Find your groove. Get your numbers. Be confident in all wind conditions. After countless hours of sailing, sail testing, and competing in the J/105, our championship winning sails will get you up to speed quickly.

Working With The Best

Our J/105 sails deliver the best results for our clients. Contact your local expert and join us at the front of the pack.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/24 US NATIONALS: LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

J/24 US NATIONALS LOCAL KNOWLEDGE

North Sails Expert Mike Ingham Explains What To Expect in Rochester

They call Rochester “Leftchester”. But of course it is not always that simple! We asked North Sails expert and Rochester local Mike Ingham what sailors should expect when they leave the docks at the 2019 J/24 US Nationals.

First, some basics:

The predominant winds are in the West quadrant (WSW to NW).

More often than not, systems come from the West quadrant, most often WSW

The thermal is NNE

The Genesee River flows North to the lake passing through Downtown Rochester before dropping considerably in altitude, passing RYC and emptying it’s silt into the lake

The racing area is typically straight North or NE from the river. It’s not quite in a bay, but the land does indent like a very open bay, so there is land from West through South to East. From West through North to East is largely exposed

The Lake is large and deep. It is around 350 miles long and 70 miles wide. The Niagara River flows into the lake on the SW corner and that water empties into the Atlantic by way of the St. Lawrence River in the NE corner

Here are some thoughts for each direction:

South Quadrant:

It’s shifty in all of the South directions.

The city of Rochester is ~8 miles up the Genesee and over 400 feet above the lake. That means the wind coming down that long hit is really unstable as it tries to mix in with the air below

Heads up puffy lake sailing.

Since the wind comes down that long hill, sometimes the puffs don’t hit the water so you don’t see them coming. Need to look and try and connect the puffs, but also need to be ready to react to whatever comes your way.

Top of the course is the most shifty because it is closer to land making the last move to the weather mark and the first move out of it pretty critical

All S directions (system driven)

Flat water

SOUTHEAST

Can happen, but is not common. Almost always associated with some rain and storm coming, but not always

Can get a lift off the right shore, but not consistently

Not a sustainable direction, it is unlikely to lock into the SE for more than half a day before something changes it

Will rarely turn into a thermal because it is associated with bad weather disrupting any land convection.

SOUTH

Relatively common system breeze

Often warm clear weather

Super shifty

Rarely any geographic pattern (like get to a shore) because relatively square to the land

SOUTHWEST

Relatively common system breeze

Can be nice clear warm weather, or can be humid with t-storms rumbling through especially in the afternoon

Can be very windy, but is relatively flat

Very shifty puffy – heads up!

West Quadrant

Common System driven

Often windy, clear

Relatively steady compared to the S winds, but still some shifts

Can have T-storms associated, especially late in the day

Out further in the lake, there can be big waves, but where we race there is a shore to the West, so that cuts down on big wave. Still choppy though.

Often very favored left because of a lift off shore and flatter water

North, Northwest System

N or NW System breeze about once a month lasting a few days (when it is windy)

Cold wind from the North

Often windy

BIG steep waves (up to 10 foot)

In the spring and summer, this is an oscillating breeze, so play the longer shifts, could be 5 min + oscillations

But in the fall, since the lake is warm and the air cold, mixing makes for big holes and puffs

Northeast System

Rare

Unstable often rainy and stormy

Does not last long

Play shifts, but don’t expect a solid pattern

Can be big waves if it does last a while because it has a very long fetch from the East end of the lake. But often does not last long enough to build up the really big waves

Northeast Thermal

Almost always a Thermal Sea breeze

Lite. It rarely gets into double digits

Like any other thermal, need a temperature differential. The lake peaks at around 65deg so it can happen even on a cool day.

The lake can “turn over”. Only the surface is warm and if the lower cool water mixes, it can get cool overnight to the mid 50’s

Flat water

Even though it is coming from the lake, it only goes out a few miles and does not have time/ distance to build up much chop

Once filled in, left seems to work more than not

Current

Surprisingly for a lake, you could see up to 1.5kts of current. Usually W to E parallel to the shore (but occasionally it inexplicably goes the other way –some kind of eddy).

You can’t predict it but can easily tell which way and how strong by watching which way the river silt exits the river on your way out.

It is caused by the bathtub effect, plus the flow of Niagara Falls (W to E). The lake is 300+ miles long and a low pressure system at one end or the other will suck the water that way, then when that pressure system goes away, the water “sloshes” back.

It is relatively even over the race course, there is rarely any local eddy or current relief anywhere because the lake gets deep quickly. You have to go right near shore and we don’t typically race there.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

DOWNWIND TACTICS

DOWNWIND TACTICS

In our previous installment we rounded the windward mark just behind our rival. In this segment North U Director Bill Gladstone explores downwind tactics against a single boat when you round close astern.

Consider this scenario: We’ve turned downwind within a couple of boat lengths of our rival – close enough that she is “under pressure.” No other boats are a concern. Pos 1 – Set the Scene. How can we pass them? Here’s How:

Pos 1 – Set the Scene- to Pos 2 – Soak

Speed First

You won’t pass anybody if you aren’t faster than they are (or at least as fast and more clever). You’ve got to focus on trim and speed first. When you’re fast then you can make tactical plays.

Basic Principles

Chase to the sides; attack when they come back. You can’t cover on both jibes. The basic play downwind is to get into attack position sailing toward the sides of the course and then attack when your rival jibes toward the middle.

Soak to Position

To get into position to attack try to match your rivals speed while ‘soaking’ a little lower. Be careful not to over-do your soak, especially in light air. If you are slow your rival may extend away beyond your wind shadow. Pos 2 – Soak

Pos 2 – Soak to Pos 3 – Attack!

Attack!

As your rival jibes, you jibe. Do not delay. There’s no, “Ready to jibe.” The team is ready! Just turn the boat – that’s the “Jibe Ho” signal (Turn with weight, not helm). This ‘simo’ jibe puts your wind shadow on your rival’s air. Their windex should be pointed at you, and yours at them…

Pos 3 – Attack

Our jibe suffocates them and they never get to full speed out of the jibe. We roll over them into the lead before they can recover. Well done!

Pos 4 – Ahead. Pos 5 – They Strike Back

They Fight Back

Alas, the leg is not over. On our next jibe our rival returns the favor, jibing on our air. Pos. 5 – Attacked. We can’t clear our air and he rolls over us. NOT Fair!

Pos. 6- Rolled!

Come Out Hot

Sometimes you can escape an attack by ‘coming out hot’ – that is, reaching up to push your apparent wind forward coming out of the jibe. Probably a good idea to warn you team before the jibe of your intentions. It won’t work if you steer ‘hot’ but don’t trim ‘hot.’

Don’t Attack

A little while later our rival jibes again. We’re in position, but we don’t jibe. Why not? Recall our basic principle of chasing to the sides and attacking toward the middle: An attack here would violate that rule and leave our rival an avenue of escape to the inside. .

Attack or Cross-Over?

Eventually we jibe Pos 8 and they jibe again. As the boats come converge we are in position to attack. In fact, we’re closer than before – a scant boat length behind now. One option is to jibe on their air. See below Pos 9S.

Option to jibe

A jibe would put our rival in our bad air and allow us to roll them. This can be strong play. One potential downside is that they may be able to block us from jibing and crossing.

Note that if we do jibe, we should jibe when still 2 – 3 lengths away. That’s close enough for our wind shadow to work yet far enough that they cannot fight back with a luff. A jibe within a length leaves us vulnerable to a hard luff where our rival can take us “to the moon” and then drive off to clear air.

Fig: To the Moon!

Cross Over

The alternative to jibing on their air is to Cross Over and Jibe. By Crossing Over and Jibing we gain control. Though we aren’t dishing out bad air we now control the path to the mark. We hold the starboard tack advantage and can jibe when we choose.

Pos 10 – Cross Over and Jibe to Pos 11 – Control

Clear Air

The Cross Over can be tricky in light air or high-performance boats as you must avoid the wind shadow of the windward boat.

Pos 10 – Clear Air

Next Play

There’s always a next play. If our rival jibes we can match their jibe to a position with clear air aft of their shadow and with an avenue of escape to the middle. If we don’t jibe they may try to Cross Over and pin us in a reversal of our current set up.

Conclusion

From here we just need to sail fast to the leeward gate. In our next segment we’ll look at Leeward Gate Tactics.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

LESSONS LEARNED FROM ROUNDING FIRST

LESSONS LEARNED FROM ROUNDING FIRST

Mike Marshall Explains Two Mental Traits That Will Help You Stay Ahead Of The Fleet

2019 J/22 Worlds 📸 Pepe Hartman

Three years after winning the 2016 J/22 Worlds, I signed on as a trimmer for the 2019 World Championship. I knew crewing would be a fresh challenge, and I was excited to help further raise the game on Raised J, owned by John Koppernaes, a team I’d sailed with in 2017.

This year’s Worlds were in Warnemunde, Germany, and our preparation strayed far from the original plan; all our practice days were blown out, so the practice race was basically our first outing—on an unproven, bottom-painted, charter boat.

What a surprise, then, to find ourselves rounding the first mark in… first.

That evening, I talked through our best approach to the regatta. “We’ve got great boat speed,” I said. “Now we just have to believe in ourselves, and know that we deserve to win.”

Sure enough, the next day we rounded the top mark in first once again—but were soon passed by the eventual regatta winners. Without being on the wrong side of a shift, what happened? Looking back in time a bit, Raised J had a tough event in the light and shifty conditions at the 2018 Worlds, and we all tend to set our future expectations by our most recent results. So this year, as soon as we rounded that first mark ahead of 30 other J/22s, the energy and excitement onboard climbed way too high. “Wow! We’re winning a race! At the World Championship!”

What we should’ve been telling ourselves instead was to keep calm, sail well, and stay in the lead—that we deserved to be there.

📸 Pepe Hartman

If turning a great start into a mediocre result sounds all too familiar, here are two traits to work on before your next big regatta.

Trait #1: Confidence

Confidence is the biggest mental asset a team can bring to the race course. Confidence in your starting ability gives you an edge over the boats around you. Confidence in your boat handling makes it possible to react more quickly to other boats’ mistakes. If you lack confidence, you may not even recognize another boat’s mistake and capitalize on it, because you’ll be too busy questioning your own abilities to recognize the errors of others—especially if it’s a top rival.

Confidence also leads to more rational decisions. If you are sure of your boat speed, you’ll be able to look past the bad shift you’re in or the bad waves you’ve just encountered. You’ll think to yourself, we’re fast, and everyone else also hits unfavorable shifts and waves. We just have to deal with these factors better than they do. Without this basic belief in your own abilities, a single wave can cause you to dramatically change the way you’re sailing the boat, making you even slower. Sure of your own skills, you’ll have fewer doubts and more definitive decision-making, which will actually make it easier to race well.

Trait #2: Learn From Mistakes

Another essential mental asset is identifying and admitting your mistakes. As cliché as it sounds, admitting that you’ve made a mistake is the first step toward moving past it. Analyze what you’ve done wrong, and have a plan to make sure you don’t make that same error again. Everyone makes mistakes, but your top competitors work hard to only make each mistake once.

Putting It All Together

Rounding first at the first mark in a World Championship proved we had equal skills and speed with the top contenders. The only thing we lacked was confidence in our own abilities. Instead of wondering how we got there, we should’ve focused on perfecting the rest of the race. Instead of getting excited, as if this great rounding was largely due to luck, we should’ve concentrated on minimizing mistakes—and learning from the ones we did make.

Sailboat racing is unique in many ways, but its mental side is the same as other sports. If you listen to top athletes around the world, you can hear in their voices the knowledge that they deserve to be at the top—as well as the humility that comes from working extremely hard to get there. We all need to keep learning, but we also need to develop the mental skills to stay on top after a great first beat.

📸 Thomas Hanf

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/70 WORLDS TOOL KIT

Get The Most From Your J/70 Racing Experience!

Teams around the world are heading to Torbay in Torquay, England for the much anticipated J/70 World Championships. Our 2019 tool kit features tips on boat speed, boat handling, crew techniques, and much more from our team of J/70 experts.

#NSVictoryList

There is no better performance test of a one design sail than the results it produces. Add your team to the #NSVictoryList!

What To Expect in Torbay

Royal Torbay Yacht Club is excited to host the 2019 J/70 World Championship. We spoke with North Sails expert Charlie Cumbley to learn what sailors should expect when they leave the docks.

Register For Free Daily Weather Forecasts

North Sails has partnered up with our expert friends at Sailing Weather Service to provide complimentary daily weather forecasts. Register now and receive these daily updates sent directly to you each morning.

J/70 Upwind Trim Tips

North Sails expert Zeke Horowitz shares important J/70 upwind sail trim takeaways from his recent experience at Long Beach Race Week.

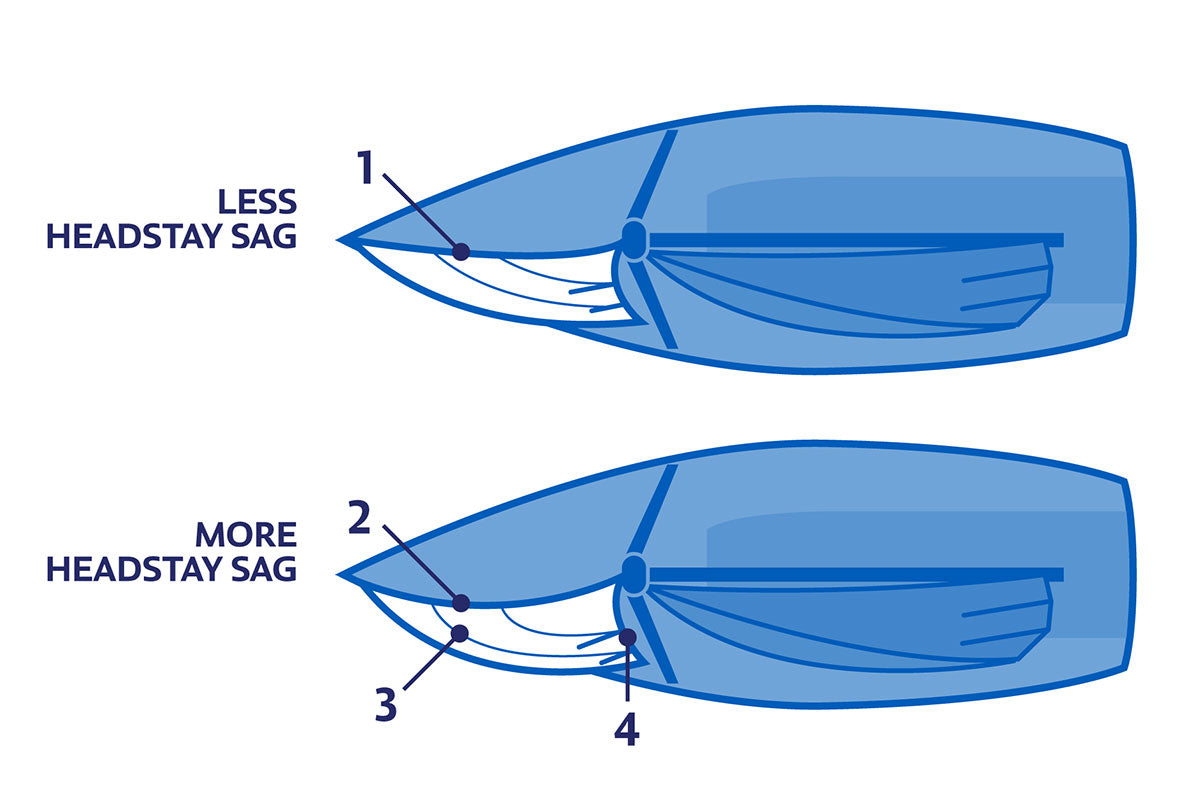

Light-Air Headstay Sag & Jib Trim

What do we look for in headstay sag to optimize jib trim for a variety of light-air conditions? World champion Tim Healy explains.

Managing Your Risks

North Sails expert Zeke Horowitz talks about placing your boat in the right place on the race course to make gains and minimize losses.

Light Air Speed Notes

A week of intense training with the Japanese teams in Newport, RI, taught Tim Healy a lot about light air tuning and trimming.

Five Downwind Modes

Displacement mode, wing-on-wing, or full plane? Understanding the J/70’s different downwind modes will help you choose the right option.

Fine Tune With North

Find your groove. Get your numbers. Be confident in all wind conditions. After countless hours sailing, testing, and competing in the J/70, our tuning guide will help you achieve race-winning speed.

Telemetry Testing for Faster J/70 Sails

A sail design can be improved, but unless you understand how to trim and tune it properly, you’re not going to get the benefit. Here’s a look at the North Sails technology that goes into designing fast J/70 sails.

Get Up To Speed

Pulling all the pieces together can be challenging. The North Sails J/70 Speed Guide leverages our expertise to help you make the most of your one design sailing.

Our Experts Make It Happen

Have questions? Contact your local J/70 expert today for more information on choosing the right J/70 sails.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/111 WORLDS TOOL KIT

Tools For Success At The J/111 Worlds

The J/111 Worlds is just around the corner. Is your team ready? This Tool Kit will help. Created just for J/111 sailors, by our J/111 expert team.

#NSVictoryList

There is no better performance test of a one design sail than the results it produces. North clients dominated the 2018 Worlds, sweeping the podium and taking eight out of the top ten spots on the scoreboard. Add your team to the #NSVictoryList!

Road To The Worlds: Establish The Plan

North Sails expert Allan Terhune describes what Team Velocity is working on right now in order to peak at the J/111 Worlds in August.

Fine Tune With North

Find your groove. Get your numbers. Be confident in all wind conditions. After countless hours of sailing, sail testing, and competing in the J/111, our tuning guide will get you up to speed quickly.

World Champion Tips

At the 2018 J/111 Worlds in Breskens, Netherlands, big-breeze speed was the key to success. Martin Dent and his team on JElvis scored nine straight bullets in the 12 race series! Here’s what worked for them.

Onboard Communication

Onboard communication for racing yachts is a key factor for performance, no matter what type of sailing. We have some suggestions to keep your boat moving through the water and around the corners more efficiently and effectively with better communication.

Working With The Best

Our J/111 sails deliver the best results for our clients. Contact your local expert and join us at the front of the pack.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/109 NORTH AMERICANS TOOL KIT

Tools For Success At The J/109 North Americans

The J/109 North Americans is just around the corner. Is your team ready? This Tool Kit will help. Created just for J/109 sailors, by our J/109 expert team.

Define Your Speed

Pulling all the pieces together can be challenging. Our brand new J/109 Speed Guide by class leader Jack Orr answers your speed and boathandling questions.

Tune For Speed

The North Quick Tuning Guide explains base settings and which sail models to use for the conditions. Learn more:

What Worked For Growth Spurt

At the 2018 J/109 North Americans, twenty teams battled for the title. We interviewed John Greifzu, owner-driver of Growth Spurt, who won the Corinthian title and second overall.

Onboard Communication

Onboard communication is a key tool for achieving peak race performance. We have some suggestions to help you communicate with your teammates more efficiently and effectively.

Working With The Best

Our J/109 sails deliver the best results for our clients. Contact your local expert and join us at the front of the pack.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

NEW J/24 TUNING GUIDE & MATRIX

Updated Tuning Numbers For The PT-2 Loos Gauge

North Sails is never satisfied when it comes to making faster sails and offering information to help clients optimize the performance of the sails. With decades of experience sailing the J/24, North expert and two-time J/24 World Champion Will Welles has released a new Tuning Guide complemented by a Tuning Matrix for the J/24 class including numbers for the new Loos Gauge Model PT-2.

“We have condensed the information and added the PT-2 numbers which were missing. I recommend to download/print the new Tuning Matrix and take with you next time you go sailing. The matrix offers a starting point based on numbers of the average boats. We left some room for you to log in your own numbers and go from there.” said Will Welles.

Open New J/24 Tuning Guide

Download North Sails J/24 Quick Tuning Matrix: Loos Gauge PRO PT2 | Loos Gauge PRO Model B

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

MOTH NEWBIE: DAN NERI LEARNS TO FOIL

MOTH NEWBIE: DAN NERI LEARNS TO FOIL

The North Sails CEO talks about his recent sailing—and swimming, and crashing—experiences

When I first saw a photo of a foiling Moth in Seahorse Magazine I did not understand what I was looking at. Since then, as I watched foiling expand from extreme dinghies to multihulls and offshore monohulls, I took the attitude that foiling came a little too late for me. I figured that, at 60 years old, my learning days were behind me. But after my Laser training partner Scott Ferguson talked me into a ride on his Moth last summer, I was hooked. Two weeks later I bought a used boat, took delivery in September 2018, and my adventures as a Moth newbie began.

Welcome newbies

Like all recreational one design classes, the Moth class is welcoming to newcomers. The experienced sailors support the bungling beginners because they, too, had to fight through the learning frustration, the broken boat parts and the bodily bumps and bruises, before gaining the skills required to get around the bay or race course. As class veteran Anthony Kotoun explains it, “We all want to get you up to speed so we don’t have to wait around or worry about you.”

On land there are no secrets. Everyone is happy to share rigging and setup ideas and even spare parts. On the water, coaching is mostly by means of “fly-bys” to demonstrate the right take-off angle, heel and sail trim. Back on shore, the best coaching of the day comes as small suggestions, words of encouragement, and reminders that everyone struggled at the beginning.

It’s complicated

The boat itself is a complicated machine. After decades of Laser sailing, I valued a high ratio of sailing time to rigging and unrigging time. The Moth is a different beast. It takes an hour to set up, and half an hour to unrig and put away.

When my new-to-me boat arrived last fall, I was eager to learn as much as I could before the Rhode Island sailing season ended. With the days growing shorter, the water colder and the westerly breeze stronger, I felt pressure to cram in learning time between the end of the work day and the beginning of night.

Setup is part of the fun

At first it seemed like everything was extremely difficult, from setting up the foils to attaching the outhaul. My first day sailing alone I had so much trouble rigging up that I ran out of daylight and never got in the water. The next day was better, even though I ended de-rigging in the dark, shivering after 30 minutes of swimming and 30 minutes of sailing and cursing at myself while looking for ring dings in the sand. But over the first 10 hours of sailing (20 hours of rigging and unrigging), I progressed from fighting the boat to a sort of affectionate truce. I learned to embrace the boat maintenance tasks as a hobby. And I accepted that rigging and foil setup time is part of the game and not just another chore.

Making it my own

Every Moth is slightly different. Mine arrived with all the required controls plus a canting rig. When I emptied the box onto the lawn I found two sets of vertical foils, a total of 6 horizontal foils, three masts and 4 different sails. These parts are not all interchangeable and for some reason, Moth parts are rarely labeled. It turns out that Patrick Wilson, the prior owner of Moth #4425, is an expert rigger and a notorious gear-head. Gradually I have modified Patrick’s Moth with an emphasis on simplicity at the expense of top end performance. Now it feels like my own boat and when I get it going I find myself marveling at the magic it produces, skimming above the surface of the bay, making no sound except the flicking of the wand. Three words keep running through my head: “This is cool.”

After about 30 hours of sailing (and 60 hours of rigging and unrigging), I can foil with confidence in the limited window of 8-14 knots. My next goal is a foiling jibe, though I know that will take a lot more time. Compared to most dinghies, building the basic skill set for the Moth is difficult, especially when you’re almost too old to learn new tricks.

Read more about Dan’s Moth adventures:

How to Build Your Moth Foiling Skills

How to Rig a Foiling Moth

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE

MAST FURLING INSTALLATION GUIDE

Key Elements of Usage and Installation

This guide is intended to help better understand the key construction elements, usage and installation of your sail. If you have any questions after reading this document and before installing your sail, please contact your North Sails representative. It is best to have two people installing the sail which can be accomplished in less than one hour. Your boat needs facing directly into the wind and ideally the wind speed should be less than 8 knots.

Step 1: Unpack your Sail

Begin by removing your North Sails Purchasers Pack including your Quality Control and Warranty information. Reserve for future reference. Locate and identify the battens (if any) and reserve for installation later.

Step 2: Attach the Mainsail Tack

Begin by unrolling your mainsail on the side deck from luff to leech. Lift the mainsail tack area and attach to your tack fitting. Your new Mast Furling mainsail incorporates a North Sails exclusive Rope Tack. This feature is designed to provide a soft and easily furled corner attachment. The sail has less patching the normal corner, but has the Spectra/Dyneema rope splayed and sewn into the sail to proved strength. Please ensure the tack rope is connected to a smooth hook or shackle to ensure durability and that no chafing occurs.

NOTE: If your mainsail has a Crab Claw Cutaway and two webbing attachment points – Please read the Stowaway Mast Furling Mainsail installation guide.

Step 3: Attach the Mainsail Clew

Lift the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and run the outhaul line through the clew block. Depending upon the type of block and the rigging of the outhaul, you may need to remove the block sheave or the outhaul line stoppers to pass the outhaul through the clew block.

Step 4: Attach the Mainsail Head

Lift the mainsail head to the mast and attach to the head of the sail to furling head swivel. The mainsail head has the same rope corner as the tack for ease of furling.

Step 5: Hoist the sail and insert Battens (if applicable)

If your mainsail has no battens, you can now hoist the mainsail all the way and furl into the mast. If your mainsail has leech battens, you will insert each batten as you hoist the sail. If your mainsail has full length battens, you will assemble the battens before hoisting the mainsail and then insert the battens after hoisting following the leech batten procedure.

Leech Batten Installation

Most Mast Furling Mainsails with Leech Battens will include Round Carbon Rod Battens. These un-tapered battens are stiff to support the leech and also able to slightly twist around the luff extrusion for easy and compact furling. The leech battens should be located on the inside of your furled sail so they do not impact the mast gap edge hen furling and unfurling. Only sails with the smallest gaps will include flat battens. Your battens will be secure into the sail with a standard Velcro leech closure. The leech (upper) end of the batten has a small plastic cap taped on to fit compactly into the closed leech batten pocket end. The bottom (lower) end of the batten has a custom metal fitting changing the shape of the batten from round to flat to best secure the batten in the sail.

NOTE: Please follow the Velcro Stuff Batten Installation Guide when inserting the Vertical Leech Battens as hoisting your sail

Full length Batten Installation

If you have ordered a Mast Furling Mainsail with Full Length Battens, you will have received your battens in segments, which need to be assembled. Simply identify the segments from the batten labels and screw together using the just joiner. Furl the sail When the sail is new, it will be stiffer than your old sail. Please keep some tension on the outhaul when you are first furling the sail, to train the patches to accept the furl. Take note to see if there are any excessive wear points and that the battens are entering the mast evenly and smoothly.

Leech Line

Your new Mast Furling Mainsail includes and Around the Clew Leech Line. The leech line is not a sail shape control but an essential tool to prevent leech flutter. The leech line will have a purchase system and Velcro closure above the clew and a cleat with in front of the clew. Your sail will either have micro-blocks or a tunnel to direct the leech line around the clew. Use the leech line to prevent leech flutter in higher wind speeds and when reefed. Excessive leech flutters can cause serious sail damage.

Sail Shape Control

You can control the depth and position of draft in your new mainsail by adjusting the halyard tension. A tighter halyard will move the draft position further forward and result in a flatter sail. When your sail is new, pull the halyard up just enough to remove any horizontal creases along the luff. In stronger breeze you will need more halyard tension.

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

J/70 UPWIND TRIM TIPS

J/70 UPWIND TRIM TIPS

Finding Your Groove In Building Pressure

📸 Bronny Daniels / Joysailing.com

North Sails expert Zeke Horowitz shares important J/70 upwind sail trim takeaways from his recent experience in California, USA at Long Beach Race Week. Zeke sailed with Jeff Janov on Minor Threat, and they tied for first place with just 18 points in the seven race regatta.

Less than 10 Knots

When the breeze is under 10 knots and you are looking for power, be sure to get up to speed by “pressing” on the jib before trying to grab any height. In these underpowered conditions, height comes from achieving flow over the keel, NOT from simply trying to point the boat higher. By pressing on the jib, you will power up the sail plan and allow your crew the chance to pressurize the weather rail. This helps achieve max flow on the keel, and your boat will start lifting.

Your leeward jib tell tale should be “nervous” most of the time and you should not sail any higher than tell tales straight back. It’s imperative to get your rig loose enough to help the headstay sag. You can always snug up the headstay by tightening the backstay if you get a little puff. Two turns off the cap shrouds and two turns off the lowers from base is probably about as loose as you should need to go (4-7 kts)*.

Trim the main so you have a nice open leech (tell tales streaming) until you are able to get weight on the rail. Once the weight is up, you can trim the main hard enough to begin seeing stall on the leech tell tales.

*The exact number of turns depends on your rig.

📸 Bronny Daniels / Joysailing.com

Above 15 Knots

When sailing in over 15 knots and chop, be decisive about your “modes” upwind. Take note of the wave angle on each tack and decide which mode you want to try on each board. For example, if one tack has the wave direction more on the bow, you may want to try a “bow down mode” to keep the speed from crashing when you hit a hard set of waves.

Bow-Down Mode

In “bow-down” mode, try centering the traveler car, pulling the backstay hard enough to just see inversion wrinkles in the middle of the main, and pulling the vang hard enough to see some inversion wrinkles down low. Play the mainsheet a lot to maintain a steady heel angle, with the jib tell tales straight back or the inside one just lifting. The name of the game here is speed, so set a target speed number and don’t let the bow come up until you’ve hit your target.

📸 Bronny Daniels / Joysailing.com

Higher Mode With Flat Boat

If the waves are more side-to, you can try a higher mode with a flatter boat. Bring the traveler car 1/3 – 1/2 of the way up. You’ll have the backstay tight, but not so tight that you see any inversion, and the vang will also be snug, but not so tight that you get low main inversion. The mainsheet will be eased a little more overall to help keep the boat flat. In this mode, you keep some power in the main with the higher traveler and fuller main, but you’ve got more twist in the leech which spills some power to keep you flatter.

It’s imperative to get the boat up to speed before trying to point, but with this mode, you can achieve more keel flow by keeping the boat flatter. At times, the driver may feel a touch of lee helm that they must push against, until the main trimmer ‘catches up’ by bringing the mainsheet in slightly. This mode is not as ‘forgiving’ but it can be lethal when the boat is up to speed in open water.

*With this second mode, you might need to try a little less inhauler to help keep the headstay straighter, since your backstay and main sheet are not trimmed quite as hard.

Learn more about North J/70 products

📸 Bronny Daniels / Joysailing.com

READ MORE

READ MORE

guides

MELGES IC37 TIPS: VOLUME FOUR

MELGES IC37 TIPS: VOLUME FOUR

Expert Notes On IC37 Boathandling and Boat Trim

📸 Melges Performance Sailboats