DN ICEBOATING: INNOVATING FOR SPEED

DN ICEBOATING: INNOVATING FOR SPEED

What does it take to go even faster than last season?

For Chad Atkins and Oliver Moore, winter means fast apparent wind sailing on their DN iceboats—whenever they can find ice and wind within driving distance of Rhode Island. We recently spoke with them to learn more about a recent speed jump made by North Sails clients. Chad finished third at the 2020 DN North Americans, his first time ever in the top five—and he was just “one bad leeward mark rounding” shy of winning the whole thing. (Tuning partner James “T” Thieler won the regatta.)

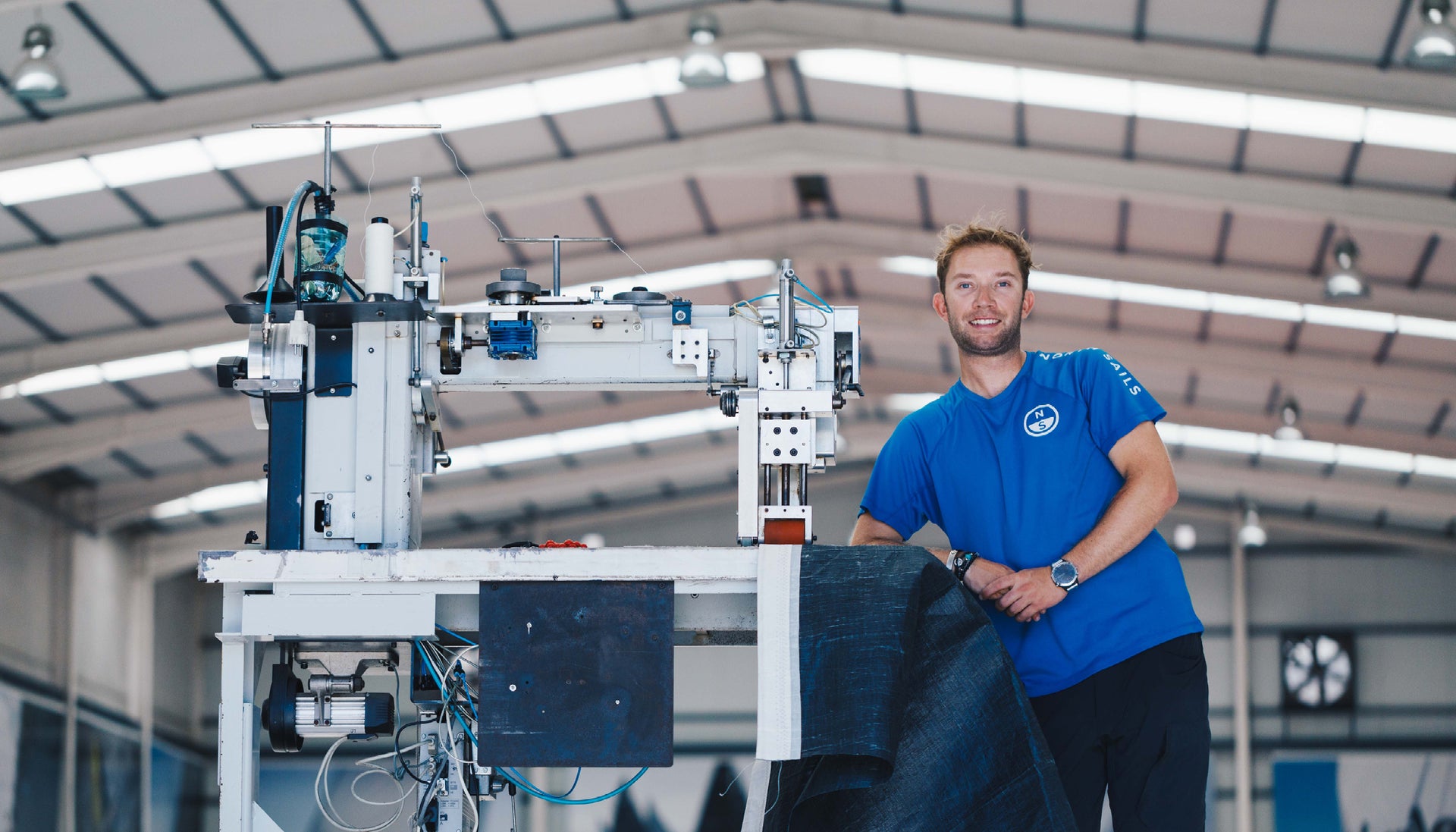

Oliver, who owns the Moore Brothers Company and builds iceboat masts, says it’s Chad’s tuning that makes him so fast. Chad, who worked with Mike Marshall to develop the North Sails DN inventory, says it’s those composite masts—and the sails designed to match them—that made his speed jump possible.

But both agree that the most significant speed gains are made long before the regatta starts, which is why iceboaters spend so much time developing and dialing in equipment to suit style, body size, and personal preference. “Most of this stuff is happening before we hit the ice,” Chad says. “Static deflection, bend testing, the development of the mast and the sails and the plank… that’s 75-80% of the speed right there.”

Oliver enjoys that part of the challenge; “It’s the most technical boat I’ve ever sailed, from a setup standpoint.” And he says Chad was the guy who got him into iceboating. “He helped set me up and got me close enough to right that I could be in the conversation. Then you can say, okay, ‘this is the effect I’m trying to achieve.’”

Mast pop

Mast bend characteristics are absolutely critical, and the goal is the same as soft-water sailing: to get powered up as low in the wind range as possible. The ideal look, though, is radically different; the mast is tuned to make it “pop” to leeward. That exerts downward pressure on the iceboat runners, acting (as Oliver puts it) “like a spoiler on a race car,” which makes it possible to push harder without losing control.

“When the breeze builds, the first to get the mast to pop wins,” Oliver says. “So at that point you want a super-soft mast. But as the breeze keeps building, you’re trying to restrain that overbend, because you’re losing power. The way you control that is all in rig geometry: adjusting your shrouds or forestay, and moving your mast.” Once you’re in the ballpark, he says, the entire range is only a couple of turns on the shrouds.

The fuselage (hull) on a DN can vary quite a bit in size and height, but both the length and stiffness of the plank (which runs athwartship and holds the shrouds) are critical. “People are measuring to make sure that when you stand on your plank, it’s bending to the exact millimeter that you think is correct,” Oliver explains. Sails are built to match each mast and plank’s combined bend characteristics, also factoring in other variables like wind strength, ice conditions, and sailor size. “Some people have four or five different sails—I’ve got two.”

Tuning up before Racing

Though the goal is to be in the ballpark speed-wise before showing up to sail, everyone fine-tunes rig tension and mast rake before each race. The mast step can move backward and forward on the fuselage up to six inches, Chad explains. “The farther forward it goes, that’s going to be a narrower triangle

With so many variables, it’s hard to compare one boat’s tuning to another. “It’s very easy to get completely confused about what’s doing what,” Oliver says, “so I try and simplify as much as I can. If you want more mast bend, ease the shrouds. If you want less, shorten your shrouds.”

Chad says that when he’s going the best, the boat “has some fight to it. I have to work pretty hard to get off the line, get the plank squatting and the mast bending, all the things that need to happen before you can really get going fast.”

If the rig tension is too soft, he says, it affects height. “You might have the same speed, but guys are going to be pointing higher. It’s a pretty noticeable difference.” If the rig’s too stiff, “people are going to be laying down and their leeches start twisting off and they’re just—gone.”

Once the boat is set up the way he wants, Chad gauges mast bend off the forestay, “to know whether to press more (shoulders back on seatback) and keep the boat lit, or ease sheet some and try to get some height upwind—or soak downwind with pressure and angle.”

Between races, sailors often swap out runners or sails to better match the conditions—which can change significantly throughout the day, as rising or falling temperatures affect the ice. “You bring all your stuff out,” Oliver says, “spares and everything, dump your toolbox on the ice. That way you can change things.”

Fast sails

Chad uses the All Purpose Power sail that he helped Mike Marshall design, or the Max Power if the wind is light and the ice soft. Oliver uses the APP as well; “I think the APP works further up the speed range and is more versatile” than older designs, adding that there’s always a tradeoff in DN sailing between versatility and optimization. “Because you can change between races, there is the temptation to have very specialized equipment for each condition—but you still need to figure out which is the right setup. I try to keep it as versatile as possible.”

What’s changed, and what hasn’t

Chad has been iceboating since he was seven. Only a year or two later, “My dad just pushed me off and I went out and didn’t come back.” He laughs. “He’s like, holy crap, I gotta build a second boat.” Since then, Chad has seen the development that used to take place in basements and garages migrate to professional shops like Moore Brothers. Composite masts are more predictable than the spruce or aluminum rigs he grew up with, making DN sailing safer—and a lot more fun. “The technology is really paying off, because you can drive the boat harder and just continue to accelerate another couple of knots.”

Oliver came to iceboating as an adult, and he admits that it’s a pretty crazy sport—especially when you factor in all the driving time that chasing ice requires. But it’s addictive, he says. “The racing at the top-end is insanely amazing—so close, you have one bad mark rounding and you lose the regatta. It’s everything that Laser racing is, but at 40 miles an hour.”

Another thing that keeps both of these guys hooked is the continuous innovation in search of ever faster speeds. “We’ve outgrown some of the smaller ponds that we used to be able to sail on,” Chad says, “because we’re going too fast. But we’re still working to go faster. The aero package part of it’s really starting to come into play, reducing that triangle between the fuselage and the forward top part of the boom… You’re never done, and it’s always fun. That’s what I love about it.” Or, as Oliver puts it: “It’s a radical thing to be going that fast, that low to the ice, crossing ten boats! One good day of sailing every three years—that’s enough to keep you coming back.”