J22 SPEED GUIDE

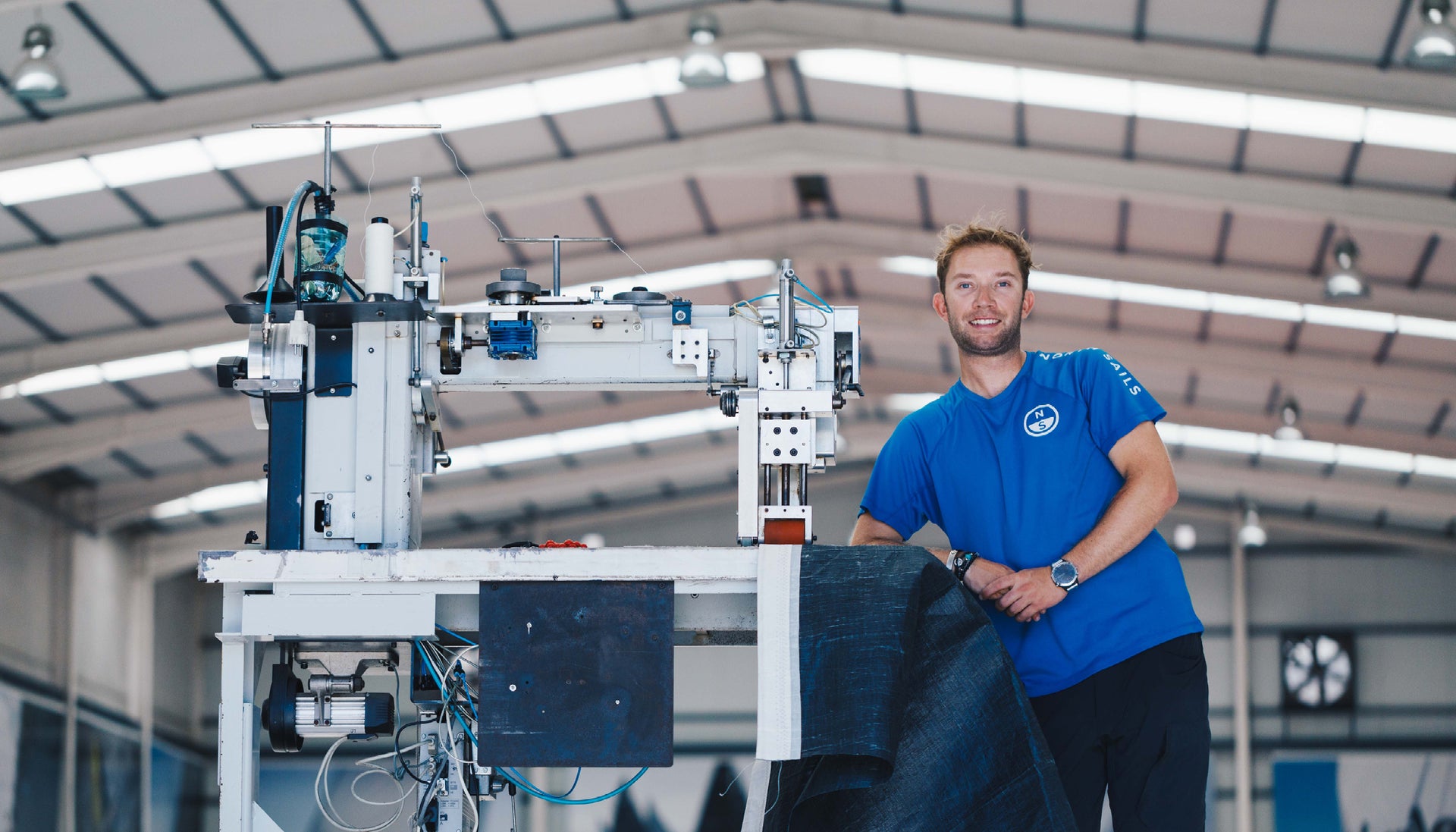

North Sails expert Mike Marshall answers your J22 speed and boat handling questions.

Who sails the J22?

The J22 class is simultaneously both international and “grassroots.” Make no mistake. The top J22 sailors are extremely talented, but at the same time, the class has a culture that’s quite approachable and down to earth. In addition to the United States and Canada, fleets are active in France, Germany, the Netherlands, South Africa, the Cayman Islands, and Jamaica.

Sailing a J22 upwind in a good breeze, hiking hard and sailing flat is fast.

J22 sailors are friendly and want to help each other sail better. On the water, people are definitely competitive, but if you ask someone on the dock what they were doing to perform so well in a certain situation, they’ll tell you. And quite a few of the people you may be asking, especially at North American regattas, have won world championships.

What’s also special about the J22 is that getting to regattas and out on the racecourse can be easier compared with many other keelboats. You only need a couple buddies to sail with you; the boat is simple to trail; and the cost of getting into the class is relatively low. Your big decision each year is which one or two new sails to buy. Put all these things together and you have a class of very friendly and likeable people enjoying an affordable game with their friends, and that creates a special vibe.

What kind of sailors do best in the J22 class?

The boats are often called “a dinghy with a piece of lead hanging off the bottom.” You need to roll tack them, and boat handling is critical to sailing fast, so dinghy sailors naturally do well. The class encourages young dinghy sailor participation with a grant program that loans a boat each season to a youth team, and these teams always do well. Of course, you still have all the technical aspects of a keelboat, so teams also need to develop the skills required to tune the rig and make sure the sail shape is right.

What is the ideal J22 crew size?

You can sail with three people or four. The weight limit is 605 pounds, and it pays to be right on the limit. Ideally, you’ll sail with your biggest person in the middle.

How physical is the crew work?

While the crew work involved in taking a J22 through maneuvers is only moderately physical, racing this boat competitively is a workout. As my friend Jeff Eiber says, “I don’t like sailing boats unless I’m working hard to do it,” and the J22meets this criterion. Jeff is happy to be a middle crew on these boats where he’ll be hiking out like you would on an Etchells. The bow person is also hiking. And the harder you hike, the faster you go.

What are your top J22 speed tips?

-

Sail the boat like a dinghy.

-

Focus on tuning and forestay length.

-

Keep the boat as flat as possible.

-

Upwind, sail as fast as nearby boats; don’t try to out-point them.

What’s involved in crewing on a J22?

When sailing with three, the helm drives and handles the mainsheet, backstay, and traveler. The middle person trims the jib and spinnaker, and also douses the chute. The bow person manages halyards, spinnaker pole, and sail controls at the mast. Sometimes the bow person is the tactician; sometimes the middle person is. When sailing with four, the bow person’s job gets split. On sets, the second person aft may feed the spinnaker out of the companionway or manage the controls for the bow person.

What should you know when buying a J22?

The first J22 was built in 1983, so many of them have been built over the years. New boats are not currently available in the U.S., but you can pick up a competitive boat for $8,000, add a couple new pieces of gear, and, with practice, compete at the top-20 level in a world championship. If you’re aiming for the top 10, you should buy a boat in the $15,000 range.

Boats with numbers above 1460 were built by U.S. Watercraft as opposed to TPI, which built the earlier boats. The newer boats have no wood in the interior and therefore need less maintenance. However, older boats can certainly compete. Boat number 677 finished in the top five at the last two world championships in the United States. Most people who join the class buy a used boat, purchase a new jib, and get on the water for $10,000 or less. If you’re on a tight budget, you can do it for half that much.

Beyond the basics, what kind of prep is needed to make a boat competitive?

If you have aspirations to be in the top 10 at the worlds, you need to prep the bottom and make sure your chainplates, mast step, and jib tracks are in exactly the right place. If that’s not your initial goal, just prep the bottom and go sailing. Bottom paint is not a problem either, but make sure it’s sanded nice and smooth. If you bought a $5,000 boat, take a close look at all the blocks. You’ll probably want to replace a few of them.

How do you transport the boat?

Although this boat has a fixed keel, it draws slightly less than four feet, so it doesn’t stand too tall on its trailer. Combining a displacement of 1,790 pounds with the weight of sails, equipment, and trailer, gives a total weight of 4,000 pounds. This means that you can haul the boat with a minivan or light SUV. One of the Canadian teams tows long distances with a Honda Odyssey. I’ve also seen European teams tow the boat with a Volkswagen Passat, but this seems a bit small to me.

What's involved in rigging and de-rigging a J22?

What I love about the J22 is that everything needed for the boat always stays on the boat. No outboard engine is required. I usually leave the shrouds attached and tuck them in. So when I pull my J22 out in the spring, I just take off the tarp, put sails in the boat, remove a bin of cleaning supplies, and put the rudder in the van. The mast is still tied down from the last time I raced, so I simply tighten the straps and drive away.

My routine at a regatta is equally straightforward. The deck-stepped mast can be put up or taken down with help from just one other person. Before launching, I usually wash the bottom and put some polish on it, and we’re ready to go. One or two of us can do all the prep work in well under two hours—or even in one hour if we’re in a rush.

What kind of inventory does North recommend and how long do sails last?

The J22 has three sails—a main, a jib and a spinnaker—and there are no restrictions on sail purchases. Jibs get tired every year from beating against the mast. Spinnakers can last two seasons if not abused. Mains might last a little longer. Most people buy a set of racing sails for major regattas, and for other racing they use their second set. When a new set is purchased, the previous new set becomes the practice set, and the cycle continues.

Our results prove that the North Sails J/22 inventory is outstanding. We’ve tested many new shapes, but have confidence that our standard designs are best across a range of conditions.

Two pins hold the J22’s mast in place.

J22 Tuning

What are the keys to setting up the rig?

First, make sure your mast is straight and centered in the boat athwartships, and then, as described in the North Sails J22 Tuning Guide, set your forestay measurement at 4’11.75”. There are two sets of numbers in the Tuning Guide, depending on the age of your boat and the type of mast step, but this position is a good starting point from which you may make further adjustments after you go sailing and get a feel for how much helm the boat generates in light and medium winds. The J22 keel position can vary by as much as 30mm fore and aft. If the keel is farther aft, you’ll likely lengthen your headstay by up to three-quarters of an inch. If the keel is farther forward, you may shorten the headstay up to three-eighths of an inch.

Be aware that you needn’t start tuning from scratch at each regatta. Once I know my mast is straight, I can leave the uppers and lowers tensioned when I unstep the mast; I just pull out the forward of the two mast pins and have someone pull out the forestay pin while I hold the mast. Because of the aft-swept spreaders, the tension on the uppers eases almost immediately. When I put the rig back up, the upper shrouds are already tuned, provided that they didn’t move when I trailed the boat to the regatta.

Upwind, whether sailing with three or four crew everyone shifts forward; even the helmsman moves ahead of the traveler.

J22 Upwind Sailing

Where does each person sit when sailing a J22 upwind?

Crew positions center around the jib trimmer, who is usually the biggest person and tends to sit just aft of the cabin house.

The driver sits as far forward as possible. On our boat, I’m far enough forward so that I can touch the winch on the cabin top. In very light air, our bow person sits right up next to the aft side of the shrouds. In big breeze, our jib trimmer moves aft half a body width, and the bow person slides back close to the jib trimmer. Having the weight together on the rail is key.

The backstay controls on our boat have been moved forward so they are between my legs in light air. When it’s windy, I’ll move back half a body width so I can play the mainsheet effectively. Our jib trimmer hikes with legs in and butt just over the rail, while the bow person hikes with legs out over the rail. The bow person hikes off the vang, so when hiking, that person pulls the vang on, and when coming back in, they let the vang off. This is in line with how you want the vang played in breeze.

In lighter air, say 7 knots, the jib trimmer will be the first to move to leeward. We don’t move the bow person if we can help it, in order to keep the rig quiet. The jib trimmer can move more smoothly and is therefore more active

What do you focus on when trimming the main and jib?

Two key things we watch on the J22 are the upper leech telltales on the main and minimizing heel. Our jib trimmer also keeps an eye on jib halyard tension, lead-car position, and the jib’s upper leech telltale.

At our lightest setting, we set jib halyard tension so we have only slight “crow’s feet” wrinkles at the headstay snaps. We position the lead car so that the foot of the jib intersects the toe rail 18 inches back from the bow. We want the foot inside the toe rail but pressed up against it. In most conditions, the jib’s top leech telltale should be flying, with just a quarter of an inch of trim needed to stall it. As the wind strength increases, these reference points remain the same, so we use more halyard to maintain little to no “crow’s feet” and move the car back because the jib is more eased. In the biggest breeze, the jib halyard is as tight as possible.

In light air, the top main telltale should always be flying. In medium air, we trim the sheet until the top telltale stalls 50 percent of the time. With increased wind, the telltale will stall less and less as we increase tension on the backstay and open up the top of the sail.

This crew is working hard to keep the boat flat even while ensuring the spinnaker is not twisted for the next set.

What are the key gear shifts to make when wind and sea state change?

The backstay and vang are hugely important controls. With a big velocity change, we’ll adjust the jib halyard. As the wind picks up, I’ll start putting more backstay on, then more mainsheet, then more backstay again, always taking slack out of the vang until I get to maximum backstay. If the wind continues to build, I’ll start to play the traveler a little, but if the traveler car ends up at the leeward seat, that’s my cue to center the traveler and start playing the mainsheet with full vang on. The bow person is already holding the vang tail because that person is hiking off the vang. The bow person tightens the vang in the puffs, and then in a lull, leans in and eases it, adding depth to the bottom of sail.

Who is in the dialogue loop and what's a typical conversation?

Our bow person calls the major waves, flat spots, puffs, and lulls. That allows me to decide whether to bear off around a wave or ride high over it, sailing with telltales up. It also allows me to be ready on the controls if I know a puff or lull is coming. Our middle person talks about relative boat speed and our positioning with other boats. Besides that, I’ll ask for more vang or cunningham, or I’ll say things like “We need to ease the jib sheet a little bit,” or “Big hike here.”

Any special considerations upwind?

As a standard rule, “Flat is fast.” Also, in big breeze, there’s a point when you can have the jib too tight. You’ll know this because, when you ease the main, you’ll see the sail start to luff due to the jib’s backwind. That’s when we’ll sometimes ease the jib sheet as much as 6 inches.

In most conditions, the J22 will be sailed at deep angles with some weather heel.

J22 Downwind Sailing

Where does each person sit when sailing downwind?

As the driver, I sit to leeward when sailing downwind, up against or in front of the traveler bar. I have four parts of the mainsheet in my hand to pump the sail. My trimmer stands to windward, weight centered over the guy block, with the leeward sheet in his leeward hand. The bow person when sailing downwind manages heel with weight movement, sitting behind the mast and generally to leeward and watching out for the boom when I pump the main.

In lighter air, the trimmer will walk in from the windward rail to add heel when needed, and the bow person will likely stay to leeward. In big breeze, our trimmer steps in and the bow person moves back a little but stays on the cabin top to hold the guy for the trimmer, often with feet in the companionway sitting on the cabin top’s leeward side. It’s important in any breeze to keep the weight as much as possible to the edges of the boat. This helps to stabilize the rocking.

What is your main focus downwind on a J22?

The main focus downwind is to make sure you’re going fast all the time. Match your speed with others before you match angle. On the J22, it’s all about momentum. As soon as your momentum starts to fade, turn up and get the boat going again. Then the middle person can move to windward and press the rail to help you bear off.

What are the keys to downwind trim for the main and spinnaker?

In light air, I trim the mainsheet and also focus on how the vang is controlling upper leech twist. In trimming the chute, we try to get the pole back as far as possible but keep the foot of the spinnaker two feet away from the forestay. Also, when the pole is fully squared, we don’t ease the clew past the forestay.

In surfing conditions, the helmsman pumps the main as the trimmer leans to windward, trimming the sheet and helping to turn the boat down the wave.

How do you shift gears on a J22 when wind and sea state change?

The boats will plane near the top of the wind range, but most of the time our mode is to drive low and, if possible, pump to surf the waves. Whether that’s possible depends on the wave state. I think of it in much the same way as I think of sailing a Laser. The more you can surf the waves, the faster you’ll go.

Who is in the dialogue loop downwind and what's a typical conversation?

My trimmer always pushes me to go lower when feeling pressure in the sheet. I also listen to the sound the boat makes going through the water, using this sound to help gauge our speed. Sometimes my trimmer says the sheet is light and we need to come up, but listening to the bow wave, I know that the boat is still moving, so I’ll hold it down for a couple more seconds.

J22 Boathandling

What's a typical start like in this class?

At the start, all the boats are set up on the line with sails luffing. It’s like going back to college sailing. Good maneuvering skills are key. Heel the boat to leeward; then flatten the boat to get going. Your goal is to open up the hole on your leeward side.

Before the start, a J22 fleet lines up with jibs luffing, each team attempting to keep way on and leave a hole to leeward for acceleration just before the gun.

Top 3 tips to starting a J22 well?

-

Set up far enough back from the line to avoid being early.

-

When sailing up to the line, over-trim the main to keep flow over the keel so you don’t slide sideways when you trim in to go.

-

Don’t pull the trigger too soon and sail down on top of boats to leeward of you.

After the gun, some boats accelerate ahead of others.

What tips can you offer for down speed boat handling?

The J22 is very much like a dinghy. The mainsail turns the boats up, and the jib pulls the bow back down. Also practice heeling the boat to turn it up (heeling to leeward) and down (heeling to windward).

What mistake slows this boat down most in a tack?

What slows you down most is the wrong rate of turn—too fast or too slow—plus not roll tacking every time.

What does each crew member do in a J22 tack?

As the driver, I stand up holding the mainsheet, hopefully with the traveler cleated on both sides. As on most smaller boats, I swap the tiller from one hand to the other behind my back, sit down on the rail, and adjust the traveler (also easing the main about an inch).

Roll tack the J22 like a dinghy, although the forward crew waits until after the tack to cross (through the slot and around the mast).

Our jib trimmer waits until the jib backwinds halfway and then releases it off one winch while holding the lazy sheet in the other hand. As the jib blows through, the excess sheet is collected either directly from the block or on the winch, depending on wind strength. No pressure should be felt on the sheet if this job is done fast enough. When the sheet is within 2 inches of final trim, the trimmer hikes out and drops the winch handle in place, ready to trim when we’re at speed.

About 60 percent of the top boats use 2:1 sheeting, with blocks on the jib’s clew. The advantage of using 2:1 is being able to sail without winch handles. The disadvantage is having a lot more sheet to get caught on things.

The bow person’s job on the tack is to avoid stepping on the jib sheets while helping to roll the boat using the handrails with butt in the air.

Then, when needed, the bow person crosses the boat, sliding between the leech of the jib and the mast. When sailing with four, the second person back can either follow the bow person around the mast or slide across the cabin top.

Any special tips for good light- or heavy-air tacks?

In light air, roll tack as hard as you possibly can. In heavy air, you need to decide when to turn fully onto a close-hauled course and when to hesitate at the end of your turn to regulate the amount of power the boat has when coming out of the tack. If you turn the boat too quickly, it will fall over. If you turn too slowly, you’ll hit a wave and slow down. Practice before the race to decide what’s best for the day’s conditions.

What mistake slows down a J22 most in a jibe?

As the driver, you have to learn the exit angle for the jibe, or your spinnaker trimmer may have difficulty flying the kite. It never hurts to practice your jibes.

What does each crew member do on a J22 jibe?

In light and heavy air, everyone rolls the boat in a jibe. As the driver, I stand up in the cockpit and grab all parts of the mainsheet along with the twing that will need to come on. Then, closing my hand tightly, I pull the twing on as I throw the boom over. In light air, I’ll roll the boat more, moving from my position on the old leeward side across to the new leeward side.

On a jibe, our trimmer is standing to windward, with a hand on the guy. Then the trimmer kneels down and uses that hand to pop the twing out of the cleat near the guy block while at the same time ducking below the boom that’s coming over. Next, the trimmer stands up or stays kneeling until ready to move to the windward rail and help flatten the boat.

Our bow person during a jibe moves across the boat to help roll it before the main comes across. Then, as the main is coming over, the bow person jibes the spinnaker pole. In big breeze, jibing the pole can be done simply standing by the mast.

What is the key to a fast spinnaker set?

When the kite goes up, make sure the clews are separated. Get the tack of the spinnaker out past the shrouds and make sure the leeward sheet is cleated, so when the tack goes forward, the clew stays aft.

The pole can be "dangled" before the mark rounding; the forward crew won’t move to snap it on the mast ring until standing up to set the chute.

Who does what in a J22 crew on a bear-away set?

The bow person keeps hiking and raises the pole from the rail. The pole is inside the shrouds and clipped to the guy up forward, so the bow person raises the pole, eases the vang, and then stands up and clips the pole on, pulling up the spinnaker halyard as fast as possible. The middle person, who has pre-cleated the spinnaker sheet to a mark, eases the jib sheet a foot while feeding the spinnaker out. When the spinnaker is halfway out, this person pulls it around with the guy as rapidly as possible until it fills. Meantime, the bow person un-cleats the jib halyard, reaches around to leeward of the mast, and gives the jib leech one good yank down. The trimmer then picks the spinnaker sheet up out of the cleat as the sail fills.

What is the key to a good J22 spinnaker takedown?

The most important tip I can offer is “Don’t wait too long.” Raise the jib and take off the pole (this spinnaker is easy to free fly). As the pole comes off the mast, the bow person remains standing, un-cleats the topping lift, and drops the pole to the deck inside the shrouds on the starboard side. Then the bow person takes the halyard in both hands waiting for the trimmer to gather half of the foot of the spinnaker on the takedown side, at which point the bow person lets go of the halyard. Quite a few lines lead to the same area at the base of the mast, so it’s important for the bow person to make sure that all these lines are cleaned up in advance.

How easily does a J22 broach?

Downwind, a broach can happen pretty easily. It typically occurs when you come out of a jibe too high or too low. So if you broach, just make sure that everyone is OK, let the spinnaker halyard down, and get the chute out of the water really fast. The boat will soon be on its feet and going again.

Any suggestions for drills to improve boat handling?

Find a buoy and do 50 circles around it in each direction. Then do 30 tacks upwind and 30 jibes downwind.

What is the coolest thing about the J22?

The class itself is the coolest thing. People who sail J22s are all extremely friendly and helpful. Everyone wants to see others succeed.