KEN READ ON OFFSHORE SAFETY

North Sails President and Offshore Veteran Shares His Offshore Sailing Tips

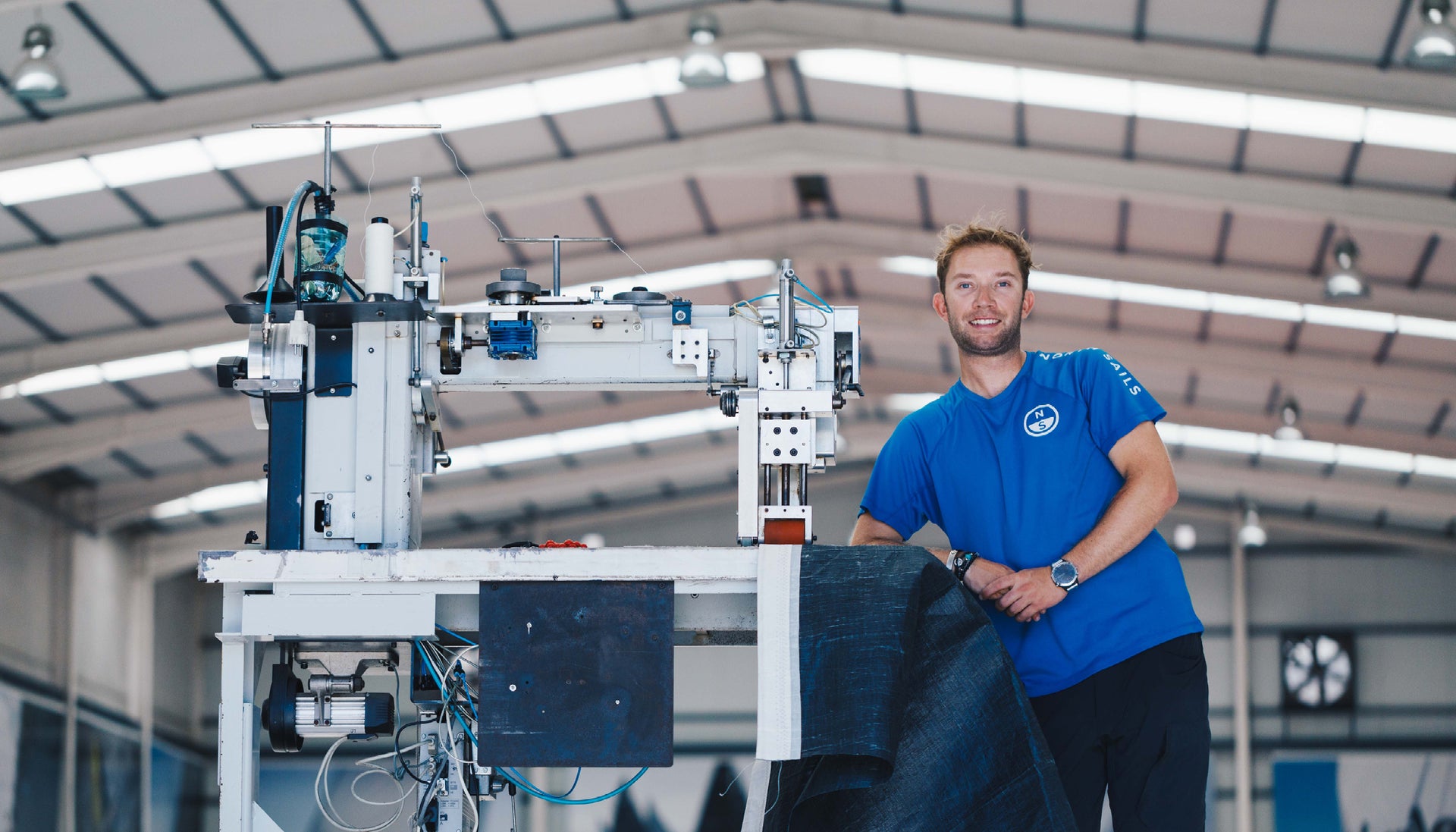

Hardcore ocean racers and coastal cruisers alike should all make safety at sea a priority. Practices from racing around the world, including the toughest conditions of the Southern Ocean, can apply to sailors of all levels and speeds. North Sails President and offshore veteran, Ken Read, shares his tips and best protocols for sailing offshore.

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

For Read, his first three Bermuda race experiences stand out as key lessons in safety at sea. The first in 1980 was onboard Fiddler, a Peterson 41, when Read and his crew hit a heavy floating cable in the open ocean. The cable wrapped itself around the keel and nearly sheared the rudder off the boat. “It opened my eyes to the unexpected,” said Read.

The second, in 1986, was onboard the J-41 Aja when one of the crew members lit the stove early in the morning to make a cup of coffee and ended up with alcohol all over the cabin. The inside of the boat, including a couple of people, caught on fire. The alcohol burned up quickly, but one crew member was left with serious burns. From that point on, Read always made it a priority to understand where extinguishers were and the type of extinguisher to use for a specific type of fire.

In 1992, aboard the S&S 66 Kodiak Read learned the importance of the man overboard drill when a crew member was ejected in the dark hours of the morning after the boat went violently over a wave.

“And we went into our fully trained, quick stop maneuver. We backed the jib, then dropped it on deck. I was driving. Mainsail trimmer Tom Scott had a flashlight on the swimmer the whole time, we spun the boat around, circled around using the mainsail alone. Once we came up alongside, four guys grabbed him, pulled him out of the water, and we were racing again in five minutes with a wet but safe crewman on board.”

If it weren’t for practicing that maneuver over and over again, there’s a chance that the accident could have been worse.

Read swears by tethers, “If you’re clipped in, you can’t go overboard. That’s the bottom line. You don’t have to use the man overboard button because that button is the last thing on earth you want to have to press.”

OUTFIT OF THE DAY

When Read first started sailing long distances offshore, he said he wished someone to told him what to bring, but now, he’s a seasoned pro. At one point, his Southern Ocean kit was made up of seven or eight layers on top and four layers on the bottom. Still, for the average sailor, his number one recommendation is a top layer with a neck seal, without a neck seal, water seeps into your base layers and can make you uncomfortable for the rest of your trip.

Clothing storage is important too; a messy boat can be an unsafe boat. Read suggests running a shock cord along the side of bunks to hang dry boots and a specific hanging area for foul weather gear that is unused by the off-watch crew.

“One thing that was important for me when I started getting really into offshore sailing is how to manage your own gear properly, so it’s not messing up the place, and safer if you need to get on deck fast.

Read also mentions the popularity of helmets with face shields, in bad weather, when water is coming over the deck, a face shield can make a difference protecting your ears and eyes.

FOOD AND DRINK

The most common misconception in offshore sailing is that bad weather is an excuse to ignore cooking, but Read knows it’s the opposite.

“When it starts getting rough, you can’t use that as an excuse not to cook. That’s the time you need to get food into people because food and water mean strength, both physical and mental. When you stop eating and you stop drinking, that’s when mistakes are made.”

As for hydrating, no matter how annoying it may be to get up in the middle of your off-watch shift to go to the bathroom, it’s worth the interruption in your rest. Dehydration is one of the most dangerous oversights in offshore sailing.

He also suggests each crew member has a designated water bottle with them at all times.

On most racer-cruisers, the galley is set up for a boat at the dock or on the mooring, but crews have to eat when underway. Read suggests preparing for the worst if using the galley on your boat is too difficult. His favorite meal offshore is a classic peanut butter and jelly in a wrap.

“It could be four in the morning, and you’d been up all night, and things are bad, and you’re at the nav station, and all of a sudden, you make yourself a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. And I swear, the whole world becomes a better place.”

Having an organized space for spices and ketchup to add a little flavor to freeze-dried or simple meals goes a long way, and sweets hidden onboard always boosts morale.

“Don’t forget a bit of sweets. When you’re halfway through a watch and somebody comes up on deck with a bag of sweets, it’s like a five-star meal. I’m not a big candy guy, but it was the greatest thing you ever possibly could have had at certain times. ”

FORGET YOUR FINE CHINA

The best possible vessel for food offshore is stainless steel bowls and utensils, they hold up and are easy to clean, especially when there is water coming over the deck. Read recalls a leg of the Volvo Ocean Race, where the shore crew had handed take-out sandwiches to the crew upon their departure. After starting the leg, they realized their metal forks hadn’t made it back onto the boat, so they were stuck with a few plastic take-out forks to last them the entire leg.

ESSENTIALS

For Read, there are a few items that you shouldn’t go offshore without, a knife you can open with one hand, a high lumen flashlight, and a headlamp with a red light setting. The red light protects you and your crew’s eyes when moving around above or below at night when others might be resting.

A high lumen flashlight could make the difference in avoiding a dangerous situation.

Read says, “there’s nothing worse than having a crummy light at night, and you’re trying to look at sail trim, look for a buoy, see something in the water, see a man overboard. Or for looking at the spinnaker sheet before putting up a new kite, whatever the case may be, don’t go cheap on a flashlight, and make sure it’s small and always in your pocket.”

As far as setting rules for your crew members? Read lives by the following:

- Get on deck five minutes before your watch starts. Never be late. Ready to go.

- Go through a full debrief with the incoming new watch members before you go below when your watch is up.

- Make your bunk when you leave it, show respect.

- Don’t get a sleeping bag wet. Ever.

- Bring a waterproof bag and keep your stuff organized! Anything left hanging around is thrown in the trash.

- Always help make food and coffee.

- Be the first to do the dirty work, lead by example, bail the bilge, others will follow your lead.

- When there is a sail change be the first out of your bunk and on deck.

- Try to schedule sail changes on watch changes.

- As a navigator, fill in as many people as you can about strategy and don’t get frustrated when answering the same question about 10 times!