KEN READ RECAPS LEG 1 OF THE OCEAN RACE EUROPE

KEN READ RECAPS LEG 1 OF THE OCEAN RACE EUROPE

First of all, it’s great to see the boats back out there.

Let’s face it. The world is itching for good things, and in the sailing world we’re just itching to get back on the water and do what we do. The Ocean Race is jumping into the season with a great idea that’s built a lot of enthusiasm in a very short period of time– the Ocean Race Europe. Simply a great showcase for the teams, the crews, and the programs to get miles in before they set off on an around the world adventure in 2022.

Practice is always good, and a vital element in preparation. Some of the boats are getting their feet wet. Newer teams, younger crews, all mixed gender, all trying to learn how to sail the boat. Other teams are pretty far down the path and have (for the most part) sponsorship reasonably secure and are a little more prepared to take on what a 56,000 mile around the planet race can throw at them. I think, for all the teams though, it’s just really great to get back out there.

Enter the IMOCA class as an additional class inThe Ocean Race, which feels more like the so-called “development era” of the past. The Volvo 70s for example were a reasonably tight box rule, but nonetheless allowed designers and teams creativity with regards to the final boat, the sail package, the setup– nearly everything. The IMOCA 60s take it one step further with only a few one-design parts like the keel fin, the mast and the rigging. But, for the most part, it’s a wide open development class. In my opinion, it feels like we’re getting back to those roots of The Ocean Race.

Yes, you could say the One-Design 65 footer class may have saved the Ocean Race a few years back when the event was looking to increase participation numbers. But now with the addition of the two different classes and the ability to choose whether it’s strict One-Design or wide open with crazy offshore development, it’s really a good thing for the race. Also it’s an outstanding thing for us as spectators to watch.

In the One-Design 65 fleet, there are very few changes to the rule. Head of operations, Neil Cox, still has to get all the boats through a mandatory checklist including any minor rebuilds in order to get them prepared to take on the rigors of offshore sailing . But besides that, it is still a strict One-Design rule with only one real “new” wrench thrown into the situation: the new A4 spinnaker.

Let’s talk about that A4 spinnaker. First and foremost, it opens up quite a few new opportunities, both tactically as well as boat speed wise. The teams are just going to have to figure out how and when to use them, and it really depends on weather systems and whether you need to go high and fast to the next weather system, or it’s more of a VMG situation where it’s optimal VMG towards the next mark.

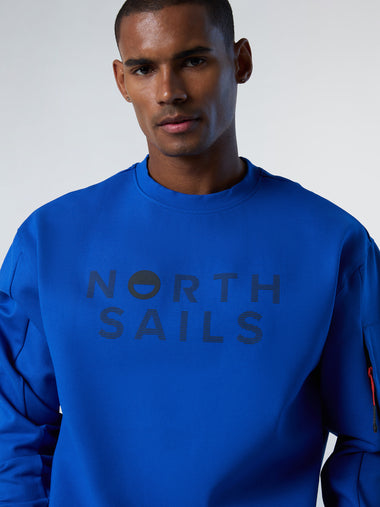

From a North Sails perspective, it’s been fun developing the A4 with the sailors right down to a brand new sail bag that was modified to help sails get in and out of the hatches with ease. They’re going to have to get out there and spend a lot of time on the water with these new sails, put them to their test, and figure out how to use them and how the boat likes to use them.

On the other hand, the IMOCAs have a crazy amount of development in their sail plans. Very similar to the America’s Cup, with the engine above the deck and the engine below the deck needing equal development time with regards to how to make a boat go fast. It’s important to remember, if the development teams only concentrate on the radical hydrofoils, then they’re going to miss out on the other half of the operation. The sail plans and the sail sizes, the aspect ratios, the anticipated wind angles, and the ability to flatten sails quickly all take on a whole new dimension when it comes to these boats. It’s the ability to have depth and size in their sail plans to get the boat popped out of the water. Not all the way out of the water, but what’s called skimming. When the IMOCA 60s are skimming, the apparent wind goes forward and as the apparent wind builds;the sailors have to have the ability to flatten the sails dramatically just using conventional tensioning devices. Enter the huge advantage of 3Di to make this happen.

It’s an interesting set of lessons to be learned over the next year in the IMOCA class, and the sailors, I think, are just on the tip of the iceberg at this stage. We’re going to see some great new concepts and designs coming out of races like this, especially when the boats are now crewed, compared to solo or Double Handed, which is more typical for the IMOCAs. It’s anticipated, according to the sailors on board, that they can sail the IMOCA upwards of 15-20% faster on average than when they’re sailed by the rule maximum crew of 5 compared to short handed. Think of that for a minute. That is a massive amount of miles gobbled up around the world just by having a few extra crew. They still had the ability to use the autopilots, which essentially are steering the boats better than a human in most conditions at this stage, and the autopilot doesn’t have nerves. When the boats get going so fast, the autopilot doesn’t know to bear off, it doesn’t know to bail out of a big wave, it just sends it. So the sailors are going to have to figure out when to pull back on throttle a little bit to keep these boats in one piece.

Anyway, it’s a fresh, brave new world for the Ocean Race. It’s just great to see it back out of the water, and we look forward to sharing some of our observations as we go along.