VIPER 640 SPEED GUIDE

North Sails expert Zeke Horowitz answers your Viper 640 speed and boathandling questions.

Who sails a Viper 640?

The Viper achieved status as a World Sailing international class, yet its sailors are mostly amateurs—pro sailors are welcome but by rule may not be paid. As a result, this class has a grassroots, sail-with-your friends feel to it. Many sailors in this sporty 21-foot keelboat have college or dinghy background, and in the Northeast part of the U.S., many come from the V-15 dinghy class. Strength helps, but sailors range in age and many women sail, including some husband-and-wife teams. Boats can sail with three or four aboard; the ideal target weight is between 500 and 600 pounds.

The Viper 640 is a fast, sporty boat that rewards a crew that loves hiking out.

What’s involved in crewing?

Most boats have three people aboard, and the skipper trims the mainsheet and vang while steering. On some boats, the middle crew may trim the main or vang at times, but otherwise is mainly hiking, calling wind pressure, and tactics. The Viper is a relatively physical boat, with a shallow and wide cockpit that requires some athleticism to cross. The spinnaker halyard has high loads, and we always like to have the strongest person pulling it up! The chute emerges forward, from a tube, and comes down the same way, with a spinnaker-retrieval line. The middle person also trims the chute on most boats.

Top three Viper speed tips?

- Hiking hard counts upwind.

- Know the tuning guide—the boat is sensitive to rig adjustments.

- Practice! Good tacks, jibes, chutes sets, and douses make a big difference.

What should buyers know when choosing a boat?

Rondar in the UK is the builder and is always building new boats. There are also plenty of used boats for sale, spanning four generations. Built in the ‘90s, the first generation boats had aluminum rigs and lighter keels. Since the carbon rig and keel weight were added in the second generation, the boats have become easier to bring up to current standards. Recent changes have provided big improvements in equipment durability, and a recent shift to a vertical rudder has enhanced the boat’s downwind capabilities in breeze. Adapter kits are available from Rondar. Overall, the class has worked hard to make it possible for older boats to remain competitive. The majority of used boats cost $15,000 to $27,000, and new boats are $38,000.

How does a Viper get around on land?

At 750 pounds and with low windage, a Viper can be towed on a trailer behind a small car. The carbon mast can be stepped and un-stepped by one or two people, and the boat can be rigged or de-rigged in an hour or less. The keel, which has a 220-pound bulb, is secured with a few bolts and is easily lifted via block and tackle in about 30 seconds. Some owners remove the keel completely from the boat when towing, putting it in their vehicle to reduce the chance of damage to the keel cassette.

How many sails are required?

The Viper 640 carries a main and a jib made of woven Dacron or Mylar laminate with polyester scrim, plus an asymmetric spinnaker made of nylon. North Sails offers a racing jib, mainsail, and spinnakers made from DK75, the slipperiest nylon sold, for easier hoisting and dousing in the spinnaker tube. For more general details, visit the Viper 640 class website.

Viper 640 Tuning

What are the keys to rig set-up?

When tuning the Viper 640 rig to race, we pay the most attention to headstay tension, shroud tension, and mast rake. Of these three adjustments, maintaining ideal headstay tension is No. 1 when it comes to maximizing speed. It’s worth noting that without a permanent backstay, mainsheet tension on a Viper is a major factor in creating and easing headstay tension. In light air, sighting up the headstay, you want about 2.5 inches of sag to leeward to power up the jib. As soon as the crew has enough wind to hike out, your goal should be to make the headstay as straight as possible; if you hit a lull and ease the mainsheet, the headstay will sag again and power up the jib in the process. Putting mast blocks in front of the mast at the partners reduces prebend, making the mast stand taller and reducing headstay sag. Typically, top boats have 2.25 to 3.25 inches of mast blocks in front of the mast.

Mast prebend is controlled by adding and subtracting mast blocks. The mast bends easily so it is sensitive to upper shroud tension. The leeward upper provides a good guide to know if your shroud tension is in the ballpark: when you’re fully trimmed in, it should just be starting to go slack. This requires a big range of adjustment – 8 or 9 full turns from light air to heavy. See the North Sails Viper 640 Tuning Guide for more detail.

What else is important?

Other speed controls like the mast butt position can be set in one place and then ignored. While the headstay length can be adjusted, it is generally kept at maximum length. Spreader brackets and tips are also adjustable, but need only be set once. (See North Sails Viper 640 Tuning Guide)

Spreader angles need only be set once, per the North Sails Tuning Guide. The upper shrouds are adjusted frequently, but top sailors adjust the lower shrouds less frequently - using them as a fine tune to keep the mast in column. They maintain just enough tension to be sure there is no leeward sag in the middle of the mast.

Viper 640 Upwind Sailing

Which is better, sailing high or fast?

On the Viper 640, we make a conscious choice at any given time between two modes of upwind sailing—faster and lower, or higher and slower. In light air, we find it’s usually better to sail low and fast due to the keel’s small surface area. With more wind, the choice often depends on the wave state. In smooth water, the boat can sail well in a high, heeled mode. When it’s choppy, we shift to more of a vang-sheeting faster and lower mode. Your crew weight and hiking ability makes a difference in your choice, and you can also use the modes in different tactical situations. For instance, it’s often beneficial to use the higher, more heeled-over mode coming off the starting line in a big fleet so that you work up to the pack on your hip and get clear to tack. Use the bow-down vang-sheeting mode when you want to get over to a puff on one side of the racecourse or roll over a pack to leeward. Our tactician keeps “moding” as a top priority and will relay the preferred mode to the driver, so that the set-up can be adjusted to get the boat as fast as possible in the new mode.

Upwind, where does the crew sit?

The rule of thumb in the Viper is to stay as forward as far you can while keeping the boat very flat. In light air, one crewmember is positioned in front of the shrouds. When everyone starts hiking, the forward crew stays there as long as they can tolerate it, then moves just aft of the shrouds. As it gets windier, everyone slides farther aft, because the boat is wider there.

How do you trim the Viper 640 mainsail upwind?

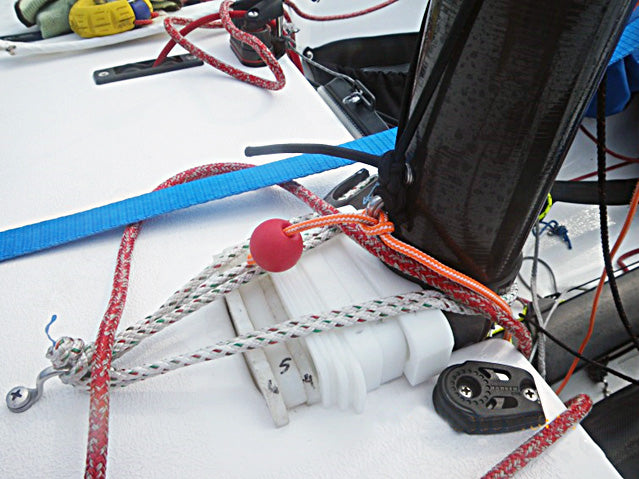

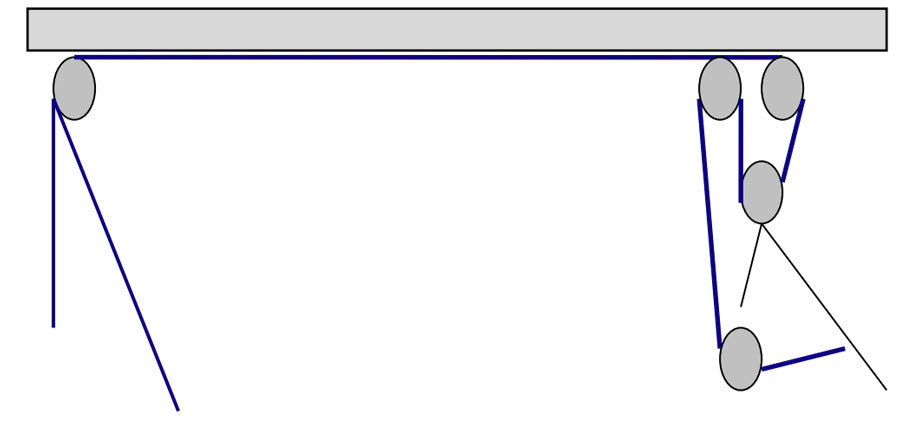

The mainsail trimmer’s primary focus is on leech tension: being sure to keep it tight enough to power the boat fully. Leech tension flattens the sail plan, tensions the headstay, and gives power to the boat. In normal conditions, we like to see the top telltale on the verge of stalling. When the breeze comes up, using the Viper’s GNAV compression vang helps maintain leech tension. Mainsheet trim requires a fair amount of strength. There are three different mainsheet set-ups, and it’s worth taking the time to study the rules on the Viper 640 class website and understand them all. If you’re in any doubt about what’s best for you, we advise that you choose the rig with the purchase aft so you can always generate the needed leech tension in a breeze.

Three mainsheet set-ups are allowed. Our default recommendation places the purchase aft.

How do you trim the Viper 640 jib upwind?

We adjust the jib leads fairly often, through a range of up to 3 or 4 inches. With more waves and more breeze, we move the lead aft to flatten the sail and/or twist the leech. In strong wind, the key is getting the sail itself flat enough to depower it while still trimming it hard. Otherwise, jib trim is fairly standard: trim in as much as you can but keep the leech telltales streaming. In some conditions, we trim in a little windward sheet to in-haul the jib, but it’s not a major factor like it is in other classes.

How do you shift gears upwind?

Between races, we often adjust shroud tension. During a race, if the wind comes up, we may add mast blocks forward of the mast and move jib leads aft. There’s also a jib halyard fine-tune, which allows us to easily add tension when the wind builds.

Who says what when sailing upwind?

Driving well in the Viper requires focus—watching telltales and waves while maintaining top boatspeed. On our boat, we leave it to the tactician to execute the game plan and determine whether to tack or duck in crossing situations. Another crewmember typically counts down the puff and lulls and relays relative speed information for nearby boats.

Keeping a constant angle of heel is fast when sailing in a breeze.

Viper 640 Downwind Sailing

How fast is the boat downwind?

Sailing downhill is what the Viper 640 is all about. In light or heavy wind, you always feel you’re going very fast. And when it’s windier, you truly are sailing fast—17 to 18 knots in a 20-knot breeze.

Where does your crew sit when sailing downwind?

Like upwind, the Viper likes weight forward to keep the wide stern sections lifted. It’s also good because the sprit is bendy and when the asymmetric spinnaker is flying, it pulls the bow up out of water. In light air, the forward crew stands in front of mast and looks aft to call puffs. The trimmer is at the shrouds, and the skipper sits on the floor, leaning against the wall of the cockpit. As it gets windy, if you’re hiking, you’re sailing too high a course. For stability, load the weather rail with your crew, with the forward person sitting just behind the shrouds.

Under spinnaker, how much heel should be carried?

The key is finding balance in the helm. Usually it comes with 5 to 8 degrees of leeward heel. Our rule of thumb is this: If you have leeward helm, push the tiller until the helm goes away. If you have weather helm, pull the tiller until it goes away. Use main trim and crew weight, along with tiller movement, to keep the boat in this mode with a balanced helm. Unlike heavier boats, the Viper never sails rocked to windward in a deep mode.

What are the keys to trimming when flying the chute?

As with any spinnaker, focus your trim on easing the sheet to the point that the luff curls. It’s a fairly flat sail, so you don’t do a lot of easing and trimming. You do need to be ready for apparent wind shifts, which can be drastic due to speed changes in puffs and lulls. The jib remains set for extra sail area but should always stay slightly eased, with the top of the jib light to avoid interrupting airflow across the spinnaker. The main always stays trimmed in pretty tight for two reasons. First, without a backstay, when it’s windy the mast can invert if you turn downwind by mistake with the sheet eased—this is another reason to sail with the lowers eased. Keeping the boomvang fairly tight also supports the mast. The second reason to keep the main trimmed in is that with the apparent wind forward, trimming with the leech twisted open at the top is faster.

How do you shift gears downwind?

The main downwind gear change relates to positioning crew weight. Move weight forward when you can, and then, when planing, move bodies aft. In waves, use a more aggressive steering mode—you’re passing the waves downwind, so use mainsheet and crew weight to maintain heel angle. Finally, be mindful of the need to stay in control and avoid wipeouts. If you feel the boat starting to wipe out, move crew weight aggressively aft to make the rudder more effective.

Viper 640 Boathandling

What are your top tips to starting well in a Viper?

The Viper 640 does not have a good “slow mode” prior to the start. You are either reaching fast or parked. You’ll need to practice steering with crew weight for those times when you’re ready for a big bearaway to get the boat going again. Like many boats, Vipers don’t go fast when sailing in a pack. Look for separation from others boats so you can go full speed after the start.

What are the keys to tacking a Viper well?

Light air tacks are the biggest challenge in the Viper; the most common mistake is not turning the boat far enough and not rolling it hard enough with your combined crew weight. It’s also important to backwind the jib. The turn takes time, and you need to wait before you roll, usually until the jib is fully backwinded. In light air, the forward person handles the jib sheets and the middle person rolls, aided by a hiking line—on our boat it’s a soft, fluffy, large-diameter line attached to lifting rings on the cockpit floor. The helmsman steers, trims the main through the tack, and aids in the roll of the boat. When it’s windy, the jobs don’t change, but you don’t usually need to roll the boat. Our crew crosses quickly and only backwinds the jib for a moment. In this condition, the helmsman needs to be sure not to oversteer the boat and give up distance to windward.

What are the keys to jibing a Viper well?

Jibing is one of the more fun, challenging aspects of sailing in this class. Big gains and losses are made on jibes. In most conditions over 6 knots, crews do a “blow-through” jibe as described below. (Remember that the jib remains set downwind.) As the boat turns, the forward crew lets the jib backwind so the chute can fill against it on the old leeward side. The trimmer tugs on the old kite sheet a couple times so the chute is slightly over-trimmed. The forward crew then gives the leech of the chute a tug until the trimmer yells to release it (when the sail is full and backwinding on the jib); the chute blows through and fills on the new jibe, and with three or four big tugs on the new sheet, it’s properly trimmed. Good footwork by the crew is key, and of course none of this works if the skipper turns too slowly or too fast. If you turn too slowly, the chute doesn’t blow through; if you turn too fast, you risk wiping out. In less than 6 knots of wind, the crew jibes the spinnaker conventionally, by simply pulling it around jib. The helmsman should turn the boat more slowly, so the trimmer can ease the chute until it’s in front of the headstay. When it’s really windy, say 18 to 22 knots, a blow-through jibe is still fastest. If you prefer something more conservative, try catching a wave, point dead downwind, and pull the spinnaker around in a more conventional jibe style. This eliminates the risk of wiping out in a blow-through turn, but it can also get tippy if you stay dead downwind so long that the boat comes off the wave.

How do you make a fast spinnaker set?

The key to a quick set is a strong middle crew and a well-lubed spinnaker and bag. The tack and and the pole-out line are the same, which means you raise the chute most of the way before setting the pole. On our boat, we make sure to mark the sheet and always have it cleated before the set. On a jibe-set, the middle person hoists (without pre-cleating the spinnaker sheet) and the pole goes out normally. As the sail is going up, the skipper turns the boat dead downwind or to a broad reach and waits for the chute to reach full hoist before making the jibe. The pole goes out as the chute goes up and the spinnaker-retrieval line comes free.

What are the keys to a good spinnaker takedown on the Viper?

Put your strongest person on the spinnaker-retrieval line, which is attached to the middle of the sail. They will use their whole body—legs, arms, and back. The helmsman should leave room to turn downwind briefly during the drop. As the helmsman turns the boat down, the trimmer releases the sheet and takes up on the retrieval line until it’s taut; then the forward crew pops the halyard and immediately lets go of the pole-out line. As the middle crew hauls in the chute, the forward crew watches out for tangles in the halyard or anything else. In light air, you can drop the spinnaker at the leeward mark; in a breeze, at 18 knots, it’s good to leave some extra time. Like other top teams, we dedicate a lot of practice to this maneuver!

How do you recover from a broach or capsize?

Although it’s not common, you can capsize and turtle the Viper 640. Recovery is like any other dinghy. It’s not difficult but it’s not fast either. On the other hand, it’s easy to recover from a broach. Make sure you move crew weight aft in the boat, release the vang, and backwind the jib. Often, that’s all it takes to make the boat bear off; if necessary, release the spinnaker halyard. Or, if you’re strong enough, you can try the “pro move” of pulling the chute around the headstay to backwind the chute as well as the jib.

What are recommended boathandling drills?

On the Viper 640, you can’t practice too many spinnaker sets, jibes and douses, including making layline calls in all wind speeds. You might bear off 15 degrees between 7 and 12 knots. Also, learn how to do hot drops when you’ve overstood and are approaching the mark at a fast angle.

The coolest thing about the Viper 640 class?

What’s great about this class is the culture of knowledge sharing among all the top sailors, sailmakers, and builders. People are easy to talk to and learn from if you’re struggling. Daily debriefs are the norm and people hang out together after racing; it’s common for sailors to eat from a pasta buffet and stand around the keg, listening in a big circle for nuggets of wisdom.