WHY IS HEADSTAY SAG FAST UPWIND IN LIGHT AIR?

WHY IS HEADSTAY SAG FAST UPWIND IN LIGHT AIR?

How Headstay Sag Affects Everything From Speed To Point

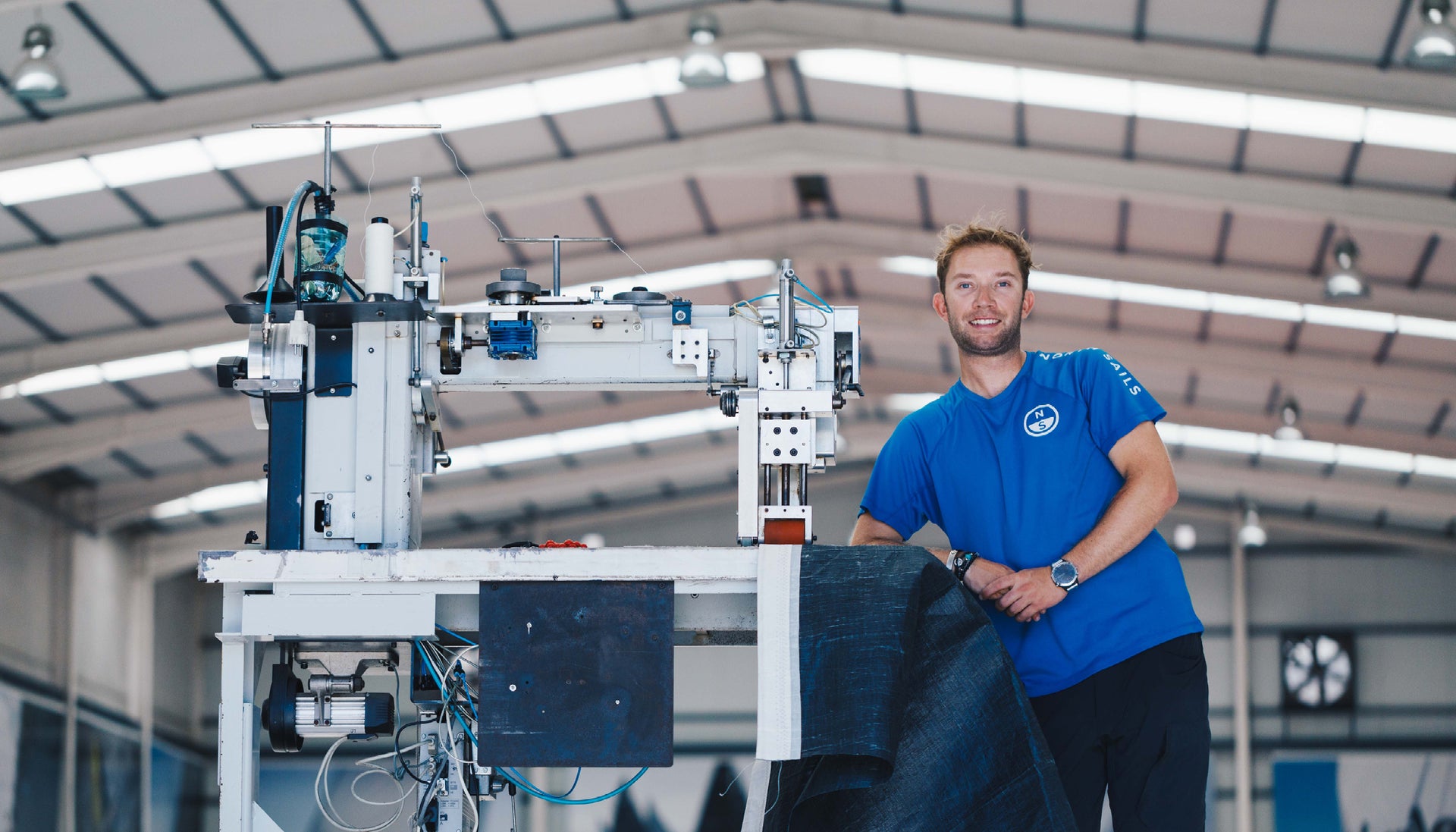

Sailboats with headstay sag often point higher and maintain boatspeed better in light-air conditions. One Design expert Tim Healy describes the rewards and the risks.

Many sailboat classes limit the number of jibs that a boat may carry, and some classes allow only a single jib. These limitations challenge competitors to find ways to maximize power in light air. One of the key methods to power up a sail is to induce sag in the headstay, also known as the forestay.

Headstay sag on a sailboat is the distance between the midpoint of the headstay if it were perfectly straight and the actual midpoint while sailing. The best way to estimate this measurement is when sailing upwind, sight up the forward side of the headstay and note how far the midpoint of the headstay has sagged when compared to the mast.

When the headstay sags, it not only sags to leeward but also sags aft, which puts the luff closer to the leech, thereby adding depth to the jib.

How to Increase Headstay Sag

The key controls for manipulating headstay sag are shroud tension, mainsheet tension, and in some cases, headstay length.

You would think that headstay length would be the primary variable, but that’s only the case on boats with keel-stepped masts, such as the Farr 40, Etchells, and Shields, that limit range of mast movement at the mast step and deck partners. On those boats, lengthening the headstay by easing the forestay turnbuckle or adding extra toggles can be an effective way to increase sag. In some classes, such as the J/24, a maximum headstay length is prescribed, limiting this adjustment. And on almost all classes, there are good and practical reasons not to overdo the lengthening of the headstay, including a negative effect on mainsail shape.

In light air, the number one adjustment for headstay sag on boats with either deck-stepped and keel-stepped masts is varying the shroud tension. More tension effectively pulls the mast aft—assuming the chainplates are aft of the mast. If the lower shrouds are farther aft, they will have the most effect; on boats with aft-swept spreaders (J/24, J/70, Melges 24), the uppers will have more effect.

The other way to induce headstay sag is to minimize mainsheet tension. If the mast is stiff, trimming the mainsheet will quickly increase headstay tension and reduce sag.

Ideally, in light and puffy conditions, when you ease the mainsheet in a lull, you’ll see the headstay sag to leeward, powering up the sail. If you don’t get that response when you ease in a lull on a Thistle, Lightning or J/70, your shroud tension is too tight.

One other way to check that your shroud tension isn’t too tight is to sight up the aft side of the mast while sailing upwind. If you see a small amount of sag to leeward in the middle of the mast, that’s a good sign that your shroud tension is right.

Easing off the rig isn’t the only way to increase headstay sag. On a Lightning, you can add a block behind your mast at the deck. On a Thistle, you can put wedges under the mast butt. On a Snipe, you can pull the mast forward at the partners. On a J/24, you can move the mast butt aft. And on an Etchells, you can do any or all of the above.

When you sag the headstay, the maximum draft in your jib moves forward. To compensate and keep the draft aft, ease halyard tension, which also creates additional power. If you increase headstay sag but the halyard remains too tight, you’ll get a big “knuckle” in the front of the sail and an entry that’s too deep, so you won’t gain the overall power you’re seeking. You should see horizontal wrinkles in the front of the sail.

What Headstay Sag Does to Sail Shape

When headstay sag is increased, the headsail becomes deeper and more powerful. If your boat is under-powered, this can make a big difference when it comes to developing speed, especially in choppy wave conditions.

The other major effect of increased headstay sag is that it effectively rotates the middle sail, changing angle of attack. The mid-luff of the sail moves to leeward as well as aft. At the same time the mid-leech rotates slightly inboard, similar to the effect of weather-sheeting, which increases pointing ability.

Once the boat becomes overpowered sag can become a liability, which is why tuning guides usually call for more rig tension as the wind increases.

What Too Much Headstay Sag Does To Sail Shape

You can have too much of a good thing. With too much headstay sag the leech will rotate inboard too far, becoming extra sensitive to sheet tension and stalling too easily. Equally problematic, the entry angle becomes too extreme; when you bear off to rebuild speed, you have to sheet out too much to power up the sail.

Another problem is that the angle of attack varies too much at the front of the sail from top and bottom. You may also see a knuckle in the front of the jib, regardless of halyard tension, and the middle of the sail becomes too flat, without generating significant power.

Light Air and Flat Water

Let’s review how this should work in two light-air conditions, starting with flat water. Here, it’s important to create power in the sail plan, and sagging the headstay is the easiest and most direct method to create depth in the jib.

This creates a scenario where the middle of the jib luff has a better angle of attack to the wind and because of that angle of attack and the inboard rotation of the mid-leech, you will be able to point slightly higher without luffing or losing flow over the front of the jib.

When you have this set up correctly, it is as important as ever to make sure the jib leech tell tales are flowing 90 to 100 percent of the time so that the airflow stays attached to the jib. That said, it is OK (and we actually encourage you) to test maximum trim by sheeting in periodically until you see the jib-leech telltales stall slightly, then ease out until fully streaming. This is your jib sheet trim range, which on some boats may be as little as 1” of sheet.

It is important to stay on top of your rig tensions in these conditions and find the settings that work best for your driving style. In addition, make sure you have some mast side sag at the spreaders, which is a signal that the mast is free to bend forward as well as to leeward. Forward bend creates a flatter main that can be sheeted tighter without stalling the leech, which will also help pointing ability.

Light Air and Chop

When chop is introduced into the picture, a loose rig is still good, but you may find that the rig will pump too much as the waves get larger. This is normal, but in order to temporarily stabilize the rig for a set of bigger waves, pull on enough backstay to snug it up. This should minimize the pumping of the rig and headstay and keep a more consistent sail shape through the chop. As soon as the patch of chop is over, release the backstay to put more sag back in the headstay.

On boats that employ in-haulers or weather sheet the jib to increase pointing ability, be careful not to overdo it. The jib leech can become prone to stalling, which can be particularly slow in waves.

We encourage you to experiment, not only with your headstay sag but with your sheeting technique. Keep notes of what works and what doesn’t, and you’ll quickly master the art of headstay sag.